李世默:特朗普顛覆“達沃斯人”三觀,習近平將其刷新

【文/觀察者網專欄作者 李世默】

若薩繆爾·亨廷頓泉下有知,他一定會忍不住笑出聲來。十幾年前,這位本時代最有先見之明的政治學家,創造了“達沃斯人”這個名詞,用以揶揄那些四海為家、信奉“跨國主義”的世界主義精英們。

達沃斯人夢想中的世界,國界將不復存在,國家這個概念將被廢棄,萬靈的選舉和市場將成為一切事物的管理機制而一勞永逸。 對他們而言,全球化不僅僅意味着經濟上的互聯互通,更是種涵蓋政治治理、國際關係和社會價值的普世願景。

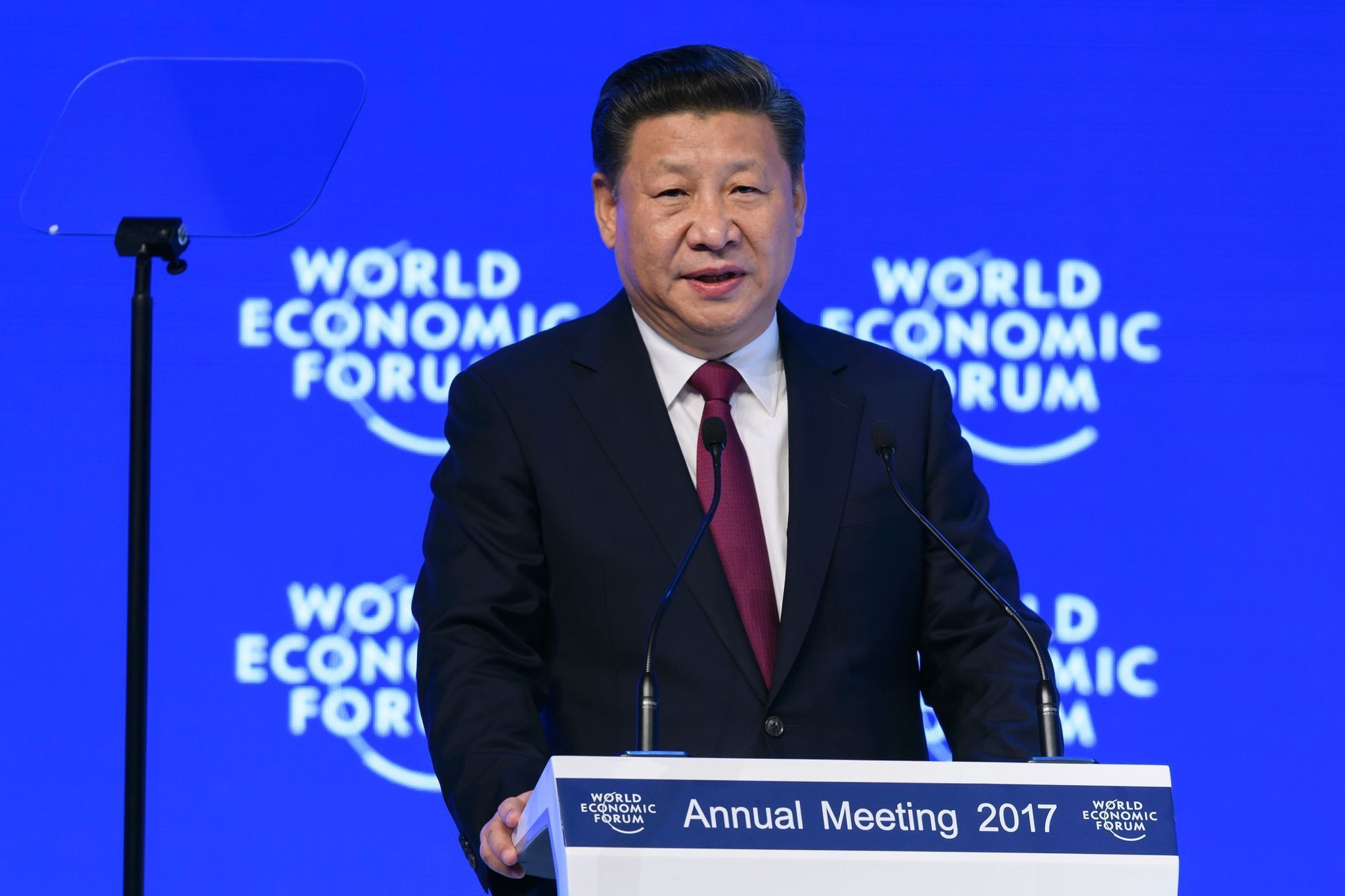

這周,在瑞士阿爾卑斯山上,達沃斯年會迎來了中國國家主席習近平,各方精英們聆聽了他的主旨演講。對達沃斯人而言,這簡直是一等一的諷刺啊(一個共產黨國家準備為他們扛起經濟全球化的大旗)!許多年來,達沃斯人看待中國的態度最多可以算是模稜兩可。在掌控世界大局的全球性精英首肯之下,中國總算加入了世貿組織、國際貨幣基金組織等統攝世界秩序的重要機構。

然而,他們對中國的否定和指責從未停止過,批評中國不承擔全球責任,甚至借民主和人權等問題不停地干涉中國內政。在這些全球精英口中,中國常常被稱作“搭便車者”,並頑固地抵制(達沃斯人制定的)全球治理規則的大一統。

中國加入世貿組織十六年後,西方國家和日本未能履行承諾,仍拒絕承認中國的“市場經濟”地位。美國本欲建立世界最大的自由貿易板塊,其主導的跨太平洋夥伴關係協定(TPP)具有針對性地把中國排除在外。

貝拉克·奧巴馬是名典型的達沃斯人,他在卸任前接受《大西洋月刊》深度採訪,警告稱中國如“……把民族主義奉為組織原則”,“作為大國卻從不承擔維護國際秩序的責任”……“只從區域勢力範圍的角度看待世界“,將導致世界動盪。

然而誰能料到,世界在六個月內發生了怎樣的變化!從英國脱歐公投到特朗普贏得美國總統大選,達沃斯人的三觀被顛覆了。 在普世化聖戰的道路上,達沃斯人把本國人民拋在身後。

套用一句小威廉·巴克利的比喻,如今,達沃斯人認為理所應當支持自己的選民們,卻站在進步的火車頭前尖叫着“停車!”達沃斯人已完全亂了方寸,以至於反過來期望習近平拯救他們的世界。作為世界第二大經濟體、頭號貿易國,中國是否會擎起全球化的大旗?也許會。但中國的全球化將迎來全新的敍事,也許不會讓達沃斯人如願。

習近平主席在主旨演講中,確定了中國保持和推進經濟全球化的承諾。但他提出以下幾點,是在座聽眾較為陌生的。

他指出,我們要適應和引導好經濟全球化,消解其負面影響。他還強調各國國情有別,應尊重發展道路的多樣性。我們必須致力於開放,但是前提是各方以包容的心態看待差異。只有如此,開放才能惠及所有人。習近平主席的演講多次提到“全球化”一詞,但幾乎每一次都在前面加上了“經濟”這個限定詞。

中國看待全球化的立場,向來都不是普世主義的。在對外交往中,中國奉行的核心原則是,各國應在不受外部干擾施壓的情況下,尋求適合自身的發展道路。正如習近平主席在演講中所説,中國是經濟全球化的受益者,更是貢獻者,中國經濟增長已成為全球經濟的火車頭,其帶動作用在經濟和金融危機時期顯得尤為突出。

中國一向堅持對發展道路擁有自主決定權,它拒絕了達沃斯人“一刀切”的全球主義方案,立足國情,有選擇地融入全球化,在一代人的時間裏使6億多中國人脱離了貧困。其他投身於全球化的發展中國家,沒有哪個取得了如此非凡的成就。

如今,全球化進程遭遇困境已是盡人皆知。然而,經濟和技術的長期發展趨勢將繼續推動世界進一步互聯互通。因此,全球治理面臨前所未有的挑戰。

習近平主席這樣説道:“中國立足自身國情和實踐,從中華文明中汲取智慧,博採東西方各家之長,堅守但不僵化,借鑑但不照搬,在不斷探索中形成了自己的發展道路。條條大路通羅馬。誰都不應該把自己的發展道路定為一尊,更不應該把自己的發展道路強加於人。”

習主席傳遞給達沃斯的信息是多元主義的,與現場大多數聽眾平日裏宣講的普世主義截然不同。習近平不是達沃斯人,但也許這才是全球化所需要的。在全球化的列車再次啓程之前,它首先需要清空重置。

(此文為作者李世默原創,翻頁看英文版全文《金融時報》)

本文系觀察者網獨家稿件,文章內容純屬作者個人觀點,不代表平台觀點,未經授權,不得轉載,否則將追究法律責任。關注觀察者網微信guanchacn,每日閲讀趣味文章。

Samuel Huntington must be laughing in his grave. More than a decade ago the prescient political scientist popularised the term Davos Man. This was the cosmopolitan proponent of “transnationalism” who dreamt of a world in which borders would disappear, states would be obsolete, and all would be governed by elections and markets. Globalisation, to him, was not just about economic interconnectedness but a universal vision encompassing political governance, international relations and social values.

This week, in an irony of the first order, the World Economic Forum welcomes President Xi Jinping, who took to the Swiss Alps to deliver the keynote address. Davos Man’s view of China has been ambiguous at best. Even as the global elites allowed Beijing into some of the institutions that govern the world order, such as the World Trade Organization and the International Monetary Fund, they continued their finger-wagging about global responsibilities and even internal matters such as democracy and human rights. China has been branded a “free rider”. It is seen as a holdout to the vision of a uniform set of rules for global governance.

The west and Japan have refused to recognise China as a “market economy”, as they pledged to do when it acceded to the WTO 16 years ago. The now defunct US-led effort to establish the world’s largest free trade block through the Trans-Pacific Partnership pointedly excluded Beijing.

Barack Obama, a quintessential Davos Man, warned in an interview with The Atlantic of a China that would “resort to nationalism as an organising principle”, that “never takes on the responsibilities of a country its size in maintaining the international order” and “views the world only in terms of regional spheres of influence”. Such a China, in his view, would create conflict.

What a difference six months makes. The Brexit vote and Donald Trump’s US election victory have turned Davos Man’s life upside down. In their crusade to universalise the world, they have left behind their own peoples. Now the constituents so long taken for granted are standing before Davos Man’s incoming train of progress and yelling “stop”, to borrow from American author William Buckley. The Davos Men are in such panic that they have turned to Mr Xi to save the day. Will the world’s second-largest economy now take up the banner of globalisation? Perhaps. But perhaps not in a way that would advance Davos Man’s narrative.

In his address, Mr Xi affirmed China’s commitment to preserve and advance economic globalisation. But he made a few points that might sound unfamiliar to his audience. He said we needed to adapt to and actively manage economic globalisation so as to defuse its negative influence. We must commit to openness, he argued — but openness can be beneficial to all only if it is tolerant of differences. He used the term globalisation several times but almost never without the qualifier “economic”.

China’s take on globalisation has never been universalist. Allowing different countries to pursue their own development paths without undue external influence has been the central theme of its engagement with the world. As Mr Xi pointed out at Davos, China has been a great beneficiary of globalisation — and a contributor, as its growth has served as a locomotive for the global economy, especially in times of economic and financial crisis.

But Beijing has always insisted on its right to determine the course of its own national development. By rejecting Davo’s Man’s one-size-fits-all globalism, it engaged globalisation on its own terms and lifted more than 600m people out of poverty within a generation. No developing country that embraced globalisation has managed anything close to this accomplishment.

Everyone now knows globalisation is in trouble. Yet trends in economics and technology will continue to drive ever increasing interconnectedness. This creates unprecedented challenges for global governance.

Mr Xi said: “China stands on its own conditions and experience. We inherit wisdom from the Chinese civilisation, learning widely from the strengths of both east and west. We defend our way but are not rigid. We learn but do not copy from others. We formulate our own development path through continuous experimentations . . . No country should put its own way on the pedestal as the only way.”

Mr Xi brings Davos a message of pluralism, as opposed to the universalism most of his audience has preached. He is no Davos Man. But perhaps this is just what globalisation needs. Before it can be restarted, it needs a reset.

Eric Li is a venture capitalist and political scientist in Shanghai.