羅伯特·謝弗:民國“沈崇”案與美國的外交政策

**【原文刊載2000年《太平洋歷史評論》****(The Pacific Historical Review),**科技從業者 林行簡/譯】

醉酒的美國士兵在亞洲強姦了一位少女,觸發了大規模的反對美軍持續佔領的示威遊行。這些亞洲的示威者們除了以美國為目標,抗議其冒犯了一位女性的尊嚴和一個國家的主權,還以本國政府為目標,抗議它允許美國在他們的國家裏駐軍。美國政府官員們手忙腳亂地修補損失,但抗議在美國大兵被判有罪後仍然繼續。

這是1995年和1996年的日本沖繩?是的,但同時也是1946年和1947年的中國。1946年12月發生在北京的一起強姦案,與最近發生在日本的事件 有着驚人的相似。該起強姦案激發了大規模的遊行示威,並明確了許多中國人對美國在二戰結束一年多之後仍在他們的國家裏駐軍的憎恨。正如其他的歷史研究正開始做的那樣,本文展示了軍國主義、對女性的暴力、以及國際關係之間的爆炸性聯繫。3

1946年聖誕前夜發生於中國的強姦案和隨後的抗議示威構成了一個案例研究:性別關係和性行為是如何損害美國在海外的形象,並因此複雜化了美國外交關係的行為。這一強姦案本身,並未導致美國防止中國共產黨在1949年取得勝利的政策的失敗。但是,它同時成為了一些問題的症狀和象徵。

這些問題是美國試圖通過軍事存在,塑造中國的政治發展的努力所固有的。這一案例也展示了在對華政策上,美國在華和在華盛頓的國務院官員們之間的分歧,以及美國國務院和軍事官員們的分歧。美國新聞媒體在國內對此事的報道,也讓我們能夠審視,美國人是否被給予足夠的機會,去了解另一個社會的人民是如何看待美國人及其軍事代表們的。

除此之外,仔細檢視被指控的強姦犯所經歷的軍事法庭審判,也説明了美國武裝力量在1947年是如何處理性暴力的問題的。雖然這一特定的強姦案已經受到了研究中國內戰的學者們的關注,並出現在中華人民共和國最近研究學運在共產主義勝利中的角色的學術文章上,該案在公開發布的美國海軍陸戰隊歷史和美國方面對那一重要時期美中關係的主流研究中,卻被忽視了。4

蘇珊·布朗米勒(Susan Brownmiller)在她的名著《違揹我們的意願》一書中,討論了對強姦的最新歷史學研究。雖然這本書最為人所知的,是其挑釁性的聲明:強姦“只是所有男人使所有女人處於一種恐懼狀態的有意識的恐嚇過程”,布朗米勒也在書中展示了戰爭與強姦的聯繫。她斷言,強姦不但表達了男人對女人的強勢,也表達了一個國家或種族對另一個國家或種族的強勢。

2013年,波蘭但澤街頭出現了俄軍士兵強姦波蘭孕婦的雕像,引發了俄駐波蘭使館的抗議(圖片來源:德國明鏡週刊)

類似地,黑澤爾·卡爾比(Hazel Carby)最近也論證説,強姦不應該被看作是一種“跨越歷史的、對女性的壓迫機制,而應被看作一種在歷史的不同時段,獲取具體的政治或者經濟意義的機 制”。所以,強姦不應該僅僅通過性別視角予以分析,發生在中國的這起強姦案還佐證了女性主義歷史學中,關注性別關係與種族民族關係之間的互動的趨勢。5

在二戰之後的餘波中,性侵犯對於美國在歐洲和亞洲駐軍的指揮官們,都是一個問題。**1946年4月,一位美國陸軍軍官在從歐洲發出的信件中寫道:“如果在人類歷史上存在着一個完全不講廉恥、不守紀律、性行為不成熟的男性,那他就是在歐洲的美軍官兵”**6。1946年6月,駐日美軍的指揮官針對美國大兵所犯下的數量驚人的罪行,下令對如下行為加強紀律處罰:偷盜、酗酒、毆打日本人、以及“對女性的攻擊“。

《紐約時報》以頭版頭條報道了這一消息:”愛徹爾伯格將軍(Gen. Eichelberger)説美軍的行為正危及佔領的使命”。1946年,在駐韓美軍指揮官約翰·霍奇將軍(General John Hodge)呼籲美軍改善在該國的行為之後,三名美軍士兵因強姦罪被判終身監禁。7

但是在中國,美國佔領軍的行為才引發了最大的危機。美國的左翼雜誌《美亞》(Amerasia)在1946年12月警告説,中國人不再把美國士兵看作是解放者,而是看作在中國日益激烈的國共內戰中,蔣介石一方的支持者。該雜誌引用了北京燕京大學的一位教授的話;該教授指控美軍犯有如下罪行:“酗酒、賭博、追逐女人、非法出售政府財產、魯莽駕駛殺人、侮辱和冒犯中國女性”。雜誌的編輯們最後下結論説,“美國在華政策正在把我們的士兵轉變成傳遞惡意的大使”。8

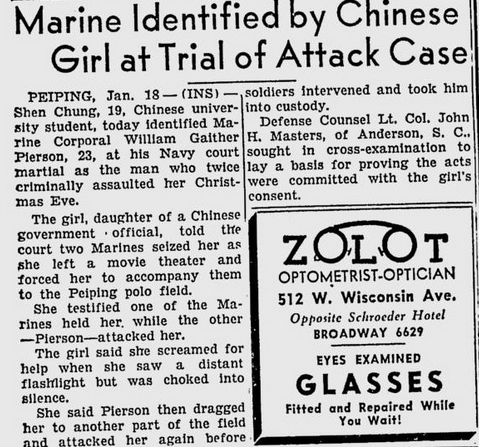

這一預測的準確性,在1946年聖誕前夜的強姦案之後,變得顯而易見了。被強姦者是19歲的北京國立大學學生沈崇,強姦者是來自南卡羅來納州的23歲的海軍陸戰隊下士威廉·皮爾遜(Corporal William Pierson),協助強姦者是列兵沃倫·普里查德(Private Warren Pritchard)。皮爾遜在1941年7月報名入伍,並在1945年延長其服役期兩年。在1946年12月那寒冷的一天裏,皮爾遜和普里查德從下午開始,就在北京的曼哈頓俱樂部,和海軍陸戰隊的戰友們在一起喝酒。

在晚上八點他們出來的時候,皮爾遜和普里查德在一家電影院外攔住了沈崇搭訕。沈崇是一位中 層政府官員的女兒,剛到達這個城市不久。皮爾遜和普里查德強迫沈崇陪着他們到附近的一處當晚空置的跑馬場。一隊中國軍隊的工人打斷了這起襲擊,但明顯出於對替皮爾遜站崗的普里查德的恐懼,這隊工人沒有直接襲擊皮爾遜,而是離開去找中美聯合警所(Joint Office Sino-American Police)的巡警。直到當晚11點半,這支特別警察力量才把皮爾遜交給了美國憲兵隊,而美國憲兵隊隨後很快釋放了皮爾遜。沈崇則被帶往市警察局接受問訊。9

沈崇

強姦的消息迅速傳遍了北京為數眾多的學生團體。該城市三所主要大學的學生們宣佈進行為期三天的罷課抗議,一萬學生參加了12月30日長達7英里的遊 行。抗議者不但要求懲罰強姦者和賠償受害的年輕女性,而且要求美國從華撤軍。在眾多的標牌和海報中,有如下話語:“你們很孤獨,你們很想家——回家去”, “美國士兵除了殺戮和強姦,什麼也不會”。10

社論和讀者來信填滿了中國的新聞媒體,它們把對強姦受害者的“侵犯”等同於對中國主權的“侵犯”。這一聯繫在反對歐洲(後來是日本)帝國主義的現代中國民族主義運動興起之後,屢見不鮮。11一個典型的例子是一位“有血性的年輕中國男子”的來信:他把這次強姦稱作“對中國女性無與倫比的侮辱”, 並認為強姦象徵着美國試圖把中國作為對抗蘇聯的殖民地的意圖。上海的30位教授簽署聲明,呼籲美國從華撤軍——歷史學家蓋爾·赫爾蕭注意到,戰後上海的美 國士兵在光顧中國妓女時製造的喧囂、酗酒、和騷亂,已經引起了當地居民的廣泛抱怨。

上海的這些教授論證説,美國駐華軍事人員犯下的強姦和其他罪行,“源自於美國把中國看作殖民地的錯誤政策”。北京清華大學的學生會也在傳單裏指控這一事件構成了“對我們學生同胞們最嚴重的威脅,以及對一個獨立民族最嚴重的輕蔑”。12該傳單已被譯成英文,包括於美國外交信函之中。

學生會列出了一長串槍擊和毆打的具體例子,以及牽涉美軍車輛的交通事故所造成的傷害和死亡。這是這一時期的中國人所不斷抱怨的。沈崇強姦案被放在了 這個清單的首位。學生們不認為這些問題是因為美國海軍陸戰隊缺乏個人紀律,而認為是帶着殖民者心態、“看不起中國人民的海軍陸戰隊士兵的心理反應的流露”。13

學生的罷課和示威迅速傳播到中國的其他主要城市。5000人於1月1日在上海和徐州舉行了遊行,第二天是南京的1500人遊行,幾天之後則是偏遠的昆明的萬人遊行。廣州的學生們據報道突破了鐵絲網,在美國領事館前舉行了示威。教會支持的燕京大學的13名教授(包括兩名美國教授),也支持了學生們的要求。清華大學的一位美國教授否認了説他反對學生抗議的報道,並聲明説如果他及時知道的話,也會加入遊行示威。14

1946年12月25日,北京大學的民主牆上就貼滿了表示要誓雪恥辱的壁報

到 1947年初,根據中國受尊敬的獨立報紙的兩次民意測驗,中國城市中產階級廣泛支持美國撤軍。在一家報紙的民意測驗中,18907名讀者中有 18716名贊成立即撤軍。15在抵抗日本殖民中國的企圖超過十年之後,在1937年的“南京大屠殺”(Rape of Najing)成為日本恐怖統治的主要象徵之後,中國人令人理解地對外國駐軍和強姦都感到敏感。16雖然一位同情學生抗議和中國共產黨的美國記者也爭辯説,示威中説美軍比日本人更壞的標牌“不公平”。17

強姦案的受審被安排在美國軍事法庭而非中國法庭,以及美國限制中國記者出席的努力,令人痛苦地復活了中國人關於帝國主義力量長久以來強加於中國的“治外法權”的記憶,而美國最近才剛剛正式宣佈放棄這一特權。18在長達一個世紀的中國反西方情緒中,“治外法權”處於核心地位。在這一問題上的看似倒退,為抗議示威活動火上澆油。不但如此,由於受害者是一位學生並來自於一個“上等家庭”,美國人將之描繪成妓女的企圖和努力讓中國人更加怒火中燒。19

階級偏見在抗議運動中也清晰可見。當一名對蔣介石持批評態度的美國領事館官員,詢問一個遊行示威的參加者,是否中國士兵也放蕩不守紀律時,他被告知:“他們的確如此,但他們只騷擾農民,不會騷擾中國知識分子”。20 學生們保護他們中的一員的願望非常的強烈,這使得沈崇案在他們眼中不同於以前對更平民化的中國人的襲擊,雖然學生們也把沈崇案同以前的類似“暴行”聯繫了起來。強姦發生在北京這一事實,也使得問題更加的複雜化——北京是中國的知識文化首都,受來自西方的影響相對較少;許多受過教育的中國人長久以來認為自己在文化上比西方人更優越,強姦案使得這一態度浮出了水面。

不但如此,美國海軍陸戰隊在北京的一所醫學院的駐軍,也毫無疑問地使中國學生們感到不安——在結束抗戰的流亡之後,他們渴望一切回到“正常”。21

北平學生舉行遊行後,位於南京的中央大學和金陵大學也加入聲援行列

位於上海的《中國每週評論》的美國編輯們,對皮爾遜強姦案進行了全面報道,他們注意到了這種階級偏見和選擇性的憤怒。這些編輯數月之後批評中國媒體忽略了中國士兵姦殺一位農村女教師的事件。編輯們補充説道:“在美國,女性無助、受庇護的維多利亞時代形象,雖然通常被方便地遺忘掉了,但在符合某些人的利益訴求時,也可以重回公眾的視野。同樣地,我們也許可以懷疑,中國古代關於女性貞潔的概念,在適當的場合下,也可以被有政治動機的人重新喚醒。”22

正如這些評論所暗示的,學生們的示威遊行也可以被詮釋成女性主義政治學家辛西婭·恩羅伊(Cynthia Enloe)最近所説的、在許多對強姦的抗議中“婦女權利對民族主義話語的從屬”。示威遊行也可以看作是一個斯派克·彼得森(Spike Peterson)和安妮·西森·魯尼恩(Anne Sisson Runyan)所説的“性別民族主義”的例子。23 例如,畢業於耶魯並且長久以來都是國民黨黨員的民族主義經濟學家馬寅初,就利用對強姦的憤怒,代表那些擔心被便宜美貨的潮水所淹沒的中國商人,在上海協助發起了抵制美貨的運動。24

但中國婦女組織對抗議活動的積極參與,提醒我們不要下結論説,中國人的憤怒主要是保守勢力重新強調傳統性別關係的努力。廣州國立中山大學的女學生們發起了抗議活動,並且有報道説,北京最初的學生示威者中有三分之一是女性,這一比例遠遠高於她們在學生總人數中的比例。屬於自由主義的民盟的婦女運動委員會,在號召參加反對美軍的運動時,把強姦稱作“帝國主義踐踏殖民地人民的習慣性動作”。在上海,包括基督教婦女戒酒聯合會在內的六個中國婦女組織,據報道在1月底,就維持在華駐軍對兩國人民的傷害,致電羅斯福總統夫人埃莉諾·羅斯福及其他人士。25

在場的美國外交官們注意到了美國大兵和中國人之間的互動對美國對華政策製造的困難。所以,此類事件也許擴大了美國國務院和美國軍方的分歧——前者在1947 年的時候傾向於反對長期駐紮地面部隊,後者則贊同駐軍。26 就在強姦發生之前一週,在重慶的美國總領事羅伯特·斯特里普(Robert Streeper),命令該地區的美軍指揮官威廉·厄普豪斯上校(Captain William Uphouse)及其隨從搬出美國領事館,因為士兵們不斷地把妓女帶進領事館,並在重慶街頭酗酒。

這些行為“負面地反映了領事館的聲譽”,而這一問題“在一波排外主義正在全中國醖釀的當前時刻”,正變得“尤其重要”。這些輕率的行徑並非只是美軍士兵一時頭腦發熱的狂亂;斯特里普對厄普豪斯抗議説,在12月 15日“五個女人在領事館過夜,我被告知,其中一個是和你過的夜,另一個是和韋伯中校(Lieutenant Webber)過的夜”。27

美媒的報道

在華的海軍陸戰隊軍官們也對強姦和示威遊行的影響表示了憂慮。1947年1月6日,A. D. 切瑞基諾少校(Major A. D. Cereghino)讓他的軍官同伴們通知在華北的美軍,關於學生示威者毆打甚至私刑處死了美國大兵的謠言“絕對沒有任何根據”。切瑞基諾尤其擔心這些謠 言會導致美軍對中國人民的“敵對”態度,從而危及美國在華駐軍的首要理由。四天之後,切瑞基諾表達瞭如下的恐懼:如果沈崇因強姦而獲取賠償,那麼許多和美軍有染的“道德低下的女孩子”就會謊稱強姦。他隨後命令士兵們“避免所有可以為強姦指控提供理由的行為和情況”。28

在天津出版的海軍陸戰隊官方週報,《華北海軍陸戰隊》,在1947年1月整個月裏,都刻意避免了所有關於強姦和學生示威的評論。只是在2月1日一篇討論美軍未來撤離事宜的長文的一段話裏,該起強姦案被提及。作為對比,該報紙正面報道了,並且極力誇大了,3月間一次由國民黨組織的學生抗議活動的出席率。該次抗議是反對所謂的蘇聯對中國事務的干涉。但強姦案的湍流最終還是進入了視野。

漫畫週刊《勺子和鹹食》(“Scoops and Salty”)以一種直白的方式講述了一個名為“阿福小姐”的年輕中國風月女子的故事——她用她的性誘惑力擾亂了兩個美國大兵的軍事任務。這個故事想要對美軍傳遞的信息清晰無誤:和中國女人的性行為會導致麻煩。雖然沒有明確提到強姦事件,一位海軍陸戰隊神父在1947年1月底為基地報紙撰稿時可能想着此事:“在華傳教士們告訴我們,美國海軍陸戰隊已經無意中對教堂的傳教工作造成了難以彌補的損害”。他補充説道,中國人“無法理解我們許多士兵的輕率行徑”。29

就強姦案本身,駐北京的美國總領事敏鋭地觀察到,“無論皮爾遜和普里查德是被定罪判刑,還是被無罪開釋,學生們都能以此證明他們反美示威和繼續抗議的合理性”。也就是説,判定有罪將證明美國大兵們的道德敗壞,而無罪開釋將會證明美國官員的背信棄義。30 美國大使司徒雷登(John Leighton Stuart)在1947年4月對中國“反美主義”的一份評估中,注意到對中國局勢和美國角色的“普遍不滿”,導致了特定事件可以成為全國範圍內的抗議的基礎。在他看來,強姦案和類似事件沒有導致普遍的反美情緒。相反的,它們成為了更深層次問題的方便的象徵和導火索。31

美國駐華外交官和華盛頓的國務院官員對示威遊行的最初反應有所不同。在他關於沈崇案的最初兩份電報裏,駐北京美國領事館的邁爾·邁爾斯(Myrl Myers)看起來在責備被強姦的年輕婦女,“教養良好的中國女子”不會在無人陪伴的情況下從晚場電影回家(事實上,沈崇是在晚上8點左右被美國陸戰隊員們攔下的)。但他很快就切換到對示威遊行一個更為政治性的評估上,強調中國政府把抗議活動歸罪於共產黨是不對的。

他的線人告訴他,大多數的示威者是自由主義的民盟的支持者。32 雖然有少數領事館官員強調共產黨也參與了遊行示威,司徒雷登大使對邁爾的評估表示了支持。甚至司徒雷登的副手,一位強烈的反共主義者,也注意到南京示威活動的領導人“智力出眾、有責任心、與共產黨毫無瓜葛”。33 國務卿詹姆斯·貝爾納斯(James Byrnes)和戰爭部的情報分析,則簡單地假定抗議示威是共產黨煽動的,這可能是因為中國共產黨在12月中旬又重新開始對美國干涉中國事務進行輿論攻擊,並升級了要求美軍撤軍的呼籲。34

與此同時,貝爾納斯敦促大使館的官員們和中國政府展開非正式的合作,以“控制事態”;這種措辭放到國民黨試圖取締學生們對強姦案的示威遊行的語境中,就帶上了不詳的含義。貝爾納斯還想要大使館協助限制美國在華新聞記者可能的破壞性報道。華盛頓的官員們起初試圖淡化示威遊行,他們告訴媒體説,示威很快就會過去,中國學生“歷史上就存在着一有機會就沉溺於示威的傾向”,尤其是將之作為一種逃避課業的手段。

當然,這一聲明對中國學生在該國的民族主義和反對帝國主 義的運動中(例如1919年的五四運動)所扮演的重要角色,是一種嚴重的侮辱。與此相反,司徒雷登則強調了示威的非暴力性,並且想要國務院避免對中國政府施加壓力,使中國政府在他正努力鼓勵國民黨和其反對者展開更有建設性的合作的時候,對遊行示威採取更嚴厲的措施。35

抗議示威在多大程度上影響了美國的政策?抗議示威當然發生在美中關係的關鍵時刻。作為對來自於國內和中國的批評的回應,哈里·杜魯門(Harry Truman)總統剛剛在1946年12月18日宣佈,美國在華軍事力量正在從1945年底巔峯時期的10萬人削減到約1萬2千人。隨後,在1947年1 月7日,正在中國以杜魯門的個人代表的身份試圖調解國共關係的喬治·馬歇爾將軍(General George Marshall),宣佈他的任務已經失敗,準備回美國。他把失敗的原因歸咎於國共雙方的強硬派。36

至少部分中國人相信在抗議示威和馬歇爾的歸國之間存在着聯繫。受人尊敬的《大公報》駐紐約市的通訊員報道説,美國的消息來源相信“學生遊行使得馬歇爾將軍感 到,美國應該重新考慮她的中國政策,否則她將不再為中國人民所歡迎”。37 國務院(現在馬歇爾是新的國務卿)在1月29日宣佈,2000名直接和馬歇爾在北京的任務相關聯的海軍陸戰隊員,包括強姦者的部隊,將很快撤離。38

1 月2日,馬歇爾協助起草了美國駐南京大使館對抗議的反應,允諾對涉案的海軍陸戰隊員進行調查,並在判定有罪時予以懲罰。馬歇爾還和司徒雷登大使以及陸戰隊指揮官塞繆爾·霍華德(Samuel Howard)會面,討論強姦案和示威遊行;彼時數千學生正在外集會。39 但馬歇爾在其1月7日的聲明中,並未討論強姦案和抗議示威;他在歸國後的 公共場合發言中,也鮮有提及這些事。40

不但如此,在馬歇爾從中國直接致函杜魯門的所謂“黃金電報”(Gold telegrams)中,也沒有什麼關於強姦案及其後果的討論;這些電報顯示,即使在強姦發生之前,就存在着把駐華陸戰隊數目削減至5000人的計劃。馬 歇爾明顯意識到美軍的存在加劇了中國的緊張局勢,但他最擔心的,還是這些部隊和中國共產主義者之間發生衝突的可能性。馬歇爾1946年12月28日的電 報,用一種急迫的口吻談到了“馬上為陸戰隊從天津和北平撤軍作準備”的必要性。

這份電報在強姦發生四天之後發出,時間上晚於北京最早的示威,但在大規模示威遊行和全國範圍內的運動開始成形之前。馬歇爾的助手,哈特·(Colonel J. Hart Caughey),的確注意到在1947年1月4日,司徒雷登從中國官員那裏感到了迅速處理強姦案的“嚴重壓力”,並且馬歇爾的工作人員隨時向他報告事態發展。但出自馬歇爾的另一位助手,G. V. 安德伍德上校(Colonel G. V. Underwood)的電報,則否認了中國媒體關於撤軍聲明源自對強姦事件的反應的報道。安德伍德還否認了抗議示威是針對馬歇爾在北京的“行政總部”,雖 然他表達了對“任何由(皮爾遜的)無罪開釋所引發的、可能會偶然涉及我們的人員的暴力”的憂慮。41

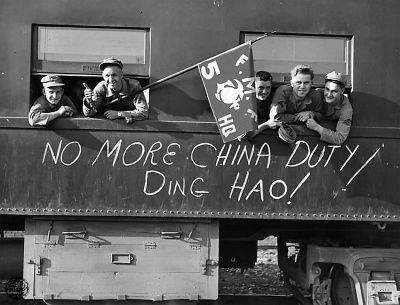

1947年,美國海軍陸戰隊撤離北平。火車上寫着:“不再有中國任務!頂好!”

所以,證明強姦案的後果促使了美軍撤離的具體文檔並不充分。但是,一個看起來合理的推論是,強姦、抗議、以及美國對美軍和中國平民之間發生進一步衝突的恐懼,都對美國減少駐華地面部隊數目的決定有所貢獻。抗議示威還限制了美國軍方在中國實施它所贊成的政策的能力,這一政策依賴於公開使用軍事力量42。在這方面,《新聞週刊》的報道説,在天津的海軍陸戰隊員對學生們的示威報以歡呼,可能是因為他們沒搞明白遊行標牌的意思;但這也可以有非常不同的解釋。很有可能,這些思鄉心切的陸戰隊員們非常明白要求他們回家的呼籲,並且相信這些抗議示威會加速他們從中國的撤離。43

正如華盛頓的國務院官員們普遍未能意識到強姦案對美中關係的影響一樣,美國媒體對學生抗議的報道,也展現了大多數美國報紙不情願從挑戰或者偏離美國官方政策的角度呈現材料的情況。事實上,回顧美國媒體對該次事件的報道,我們可以發現,貝爾納斯的觀點佔據了主流。美國媒體不顧美國駐華記者發來的數量充足的電報,把強姦受害者和學生抗議者的痛苦做了最小化處理。示威遊行因此看起來離譜、不理性、並且充滿威脅性。

例如,《華盛頓郵報》在1947年1月1日對抗議示威的首次報道中,把示威者簡單地描繪成反對美國,而未能提及他們正在對一起強姦指控作出反應。第二天, 《郵報》引用了合眾社的一封快報,以“學生們該負責:中國人在上海毆打美國軍官”為標題,把注意力完全集中到了抗議示威中一個美國人受到傷害的事情;只是在文章的第九段,這些抗議示威的原因才被説明。直到第四天的報道,《郵報》才把強姦的指控放到了第一段。44

《郵報》最近才剛剛在社論裏,對杜魯門實行普遍的男性軍事訓練的計劃表示了讚賞。這部分是因為要解決《郵報》所稱的“國家的男子漢氣概的大問題”:這一概念清晰地把軍事力量和性能力等同了起來,並且可能預兆着“對共產主義太軟弱”的冷戰憂慮。然而,《郵報》也發表了專欄作家馬爾韋納·林賽(Malvina Lindsay)的文章,警告年輕美國大兵的性行為可能會使歐洲人和亞洲人對美國性格以及美國社會的幻想發生破滅。

在沒有特別提及皮爾遜強姦案和學生們的抗議的情況下,林賽指控美軍軍官們在這些問題上為他們的部隊樹立了惡劣的先例。林賽還關注了海外性亂交的後果:“被佔領國數千沒有名字、身無分文的混血兒,將會在未來對離開的征服者的自私和淫蕩作出證詞”。45

**一些報紙,包括《費城問詢報》、《洛杉磯時報》、以及《基督教箴言報》,甚至拒絕使用“強姦”和“涉嫌強姦”等詞彙;它們把事件用“襲擊”、“親密”、以及“涉嫌行為不檢”等委婉説法加以掩飾。**一位《洛杉磯時報》的專欄作家承認“我們有的士兵可能越過了舉止端正的邊界”,但除此之外,他卻未能向讀者給出學生抗議示威的根本原因。 有些報道把抗議完全歸咎於中國共產主義分子的組織,但這忽略了示威所受到的廣泛歡迎,以及非共產主義的中國媒體對示威的支持。其他媒體,在諸如“中國學生聯合起來與大學裏的反美情緒作鬥爭”這樣非常不準確的標題之下,誇大吹噓了中國學生一個支持國民黨和美國的小規模“反運動”,似乎這些人更能代表中國的觀點。47

《新聞週刊》沒有把事件描繪成美國士兵虐待當地人的例子,反而把事件描繪成當地人虐待美軍的例子。類似地,持孤立主義立場的《芝加哥論壇報》把中國人的“下流語言”和暴徒般的行為,與駐華美軍的“偉大自制”做了對比;《華爾街日報》的一位專欄作家則和許多人一起,把抗議示威看作是對美國在戰時對華慷慨援助的忘恩負義的明證—— “‘反向租借’的一種特殊形式”。48

可能最帶偏見的報道出現於亨利·盧斯(Henry Luce)主辦的、支持蔣介石的《時代》雜誌。《時代》雜誌剛剛用弗雷德雷克·格魯恩(Frederick Gruin)替換掉了它的戰時駐華通訊員,西奧多·懷特(Theodore White);雜誌的外國新聞則通常由在紐約的惠特克·錢伯斯(Whittaker Chambers)撰寫,此人是著名的反共人士。在1947年的第一期裏,《時代》雜誌把蔣介石的政府描述成日益穩定、受歡迎、民主、並且值得接受美國的軍事援助。

1945年日本投降後,蔣介石成為某期《時代》週刊的封面

發生在中國的大規模反美反國民黨的抗議示威,對這一看法提出了挑戰。《時代》雜誌繞來繞去令人費解的邏輯則解釋説,在中國和其它國家裏,那些要求美軍撤離的人,嘴上説的和心裏要的不是一回事。恰恰相反,他們真正想要的,是美軍在他們國家更強烈的存在。49 這個論證的基礎,看起來是一個沒有説破的把國際關係比作家庭的隱喻:智慧的爸爸(美國)知道孩子(在此案例中,是中國)的反叛只是一種要父母予以更大指導的請求。50

《紐約時報》和《紐約先驅論壇報》都有自己的駐華記者。他們的報道比絕大多數媒體都全面,並且更廣泛地引用了中國出版物和談論政治的人物。他們還把示威遊行與學生聯繫了起來。中國學生在中國民族主義的歷史上、以及反對外國的運動中,扮演了重要的角色。《紐約時報》和《先驅論壇報》的報道還注意到了對美軍行為的其他不滿,以及軍事法庭作為治外法權重新開始的信號所帶來的更廣泛的問題。51 但即便是這些報道,也費盡周折地稱讚了美軍士兵的行為,尤其是與滿洲的蘇軍士兵相比較。據《紐約時報》報道,滿洲的年輕中國女子偽裝成男孩子,以避免蘇軍士兵的性掠奪。到了1月6日,《先驅論壇報》開始強調抗議示威帶着 “清晰的左翼影響的記號”;通訊員阿奇博爾德·斯蒂爾(Archibald Steele)把來自延安的共產主義分子對強姦的宣傳,同最近摧毀掉的納粹宣傳機器相提並論。52《先驅論壇報》最後用中國學生與美軍士兵之間相互不信任和憎恨的原因,作為社論的結尾。這篇文章還算深思熟慮,除了要求美國繼續在華駐軍,以應對蘇聯侵犯的呼籲——這最終會落實學生們對美國利用中國實現自己目的的指控。53

美國共產黨的《工人日報》不令人意外地對抗議和軍事審判提供了前後一致和具有同情心的報道,其報道的基礎主要是電傳報道。早期的一篇社論否認了中國和其他國家要求美國撤軍的人是“反對美國”;該社論論證説,這些對民主和獨立的要求與美國的原則一致。54

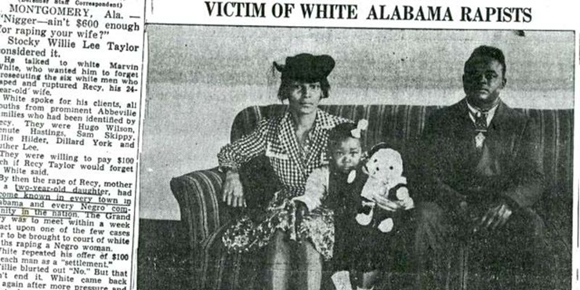

在紐約市的左翼-自由主義日報《畫刊》,也在1月初對沈崇案給予了重點報道,但關於抗議的兩篇專題文章提出了不同的觀點。詹寧斯·佩裏(Jennings Perry)是一位從田納西發稿的《畫刊》常駐專欄作家。他把對跨種族強姦感到憤怒不已的中國“暴徒”,與他所見過的美國南方白人暴徒相提並論;這些南方白人會被白人女性為黑人所強姦的宣稱刺激得暴跳如雷。對於佩裏而言,美國人在國內外對待有色人種的方式,值得所有在海外承擔義務的白種人模仿學習;這幾乎就是某種詩意般的正義。

他警告説,在對中國學生們作出太過嚴厲的判斷之前,美國人應該將心比心地審視他們自己的行為。他也意識到,在中國的學生示威者並非濫用私刑的暴徒,因為“沒有私刑發生”。但他的主要觀點是,中國人對強姦指控的利用和美國南方白人類似,他也明確聲稱他知道這些指控。這一觀點也許反映了一個由蘇珊·布朗米勒所提出的、更為普遍的模式:自由主義者對跨種族強姦的指控感到懷疑。這種懷疑的背景,是進步主義者長期堅持的、對三四十年代大加渲染的黑人強姦白人婦女的指控的抗議。這些被定罪的強姦案包括斯科茨伯勒小夥(the Scottsboro Boys)強姦案和其他一些案子。55

美國某報紙在150年代對跨種族強姦的報道

《畫刊》還刊登了合眾社發自中國的專題報道。該報道從中國學生的角度看待抗議示威,雖然一個未説的假設是“這個中國學生”是男性。這篇文章注意到了學生們在中國20年代抗議英國和30年代抗議日本中的重要性;文章隨後解釋説,對強姦的抗議示威在當時是一種能夠為人所理解的反應——當時中國學生的生活條件非常糟糕,宿舍裏沒有暖氣,食物也不夠,而相對寬裕的外國士兵們則在他們的城市裏橫衝直撞,並且有中國裔的“吉普女郎”或其他女性中國同伴陪伴。

年輕的中國人對持續內戰所造成的國家發展的停滯而鬱悶沮喪;他們自然地把憎恨發泄到了外國士兵身上。56《畫刊》的若干讀者對這兩篇文章作出了回應。一位讀者攻擊説這些學生是種族主義分子,而另外兩位讀者——其中包括一位居住在麻省劍橋市的中國人——則譴責把中國學生當作南部私刑暴徒的類比;他們強調説,學生們是在抗議美軍的存在,而後者在當時的中國並無用處。57

賓夕法尼亞州一個小城市的報紙,激情四溢的《約克公報》,也對中國學生的抗議進行了全面而富有同情心的報道。該報紙也是主要依靠電傳報道獲取信息。這再次顯示了是美國國內的編輯們,而非來自中國的報道,決定着故事的傾向。沒那麼聳人聽聞的標題會造成巨大的不同。例如,《洛杉磯時報》把一條報道作為頭條:“中國學生毆打美國人”,但報道忽略了示威的原因。

《約克公報》把同樣的故事也作為頭條:“中國學生要求美軍撤出中國”,報道還清楚地解釋了強姦事件。《約克公報》的另一篇文章注意到了上海的教授們反對美國對華“半殖民地”政策的集體聲明。這在紐約市以外的報紙中,是為數不多的嚴肅對待中國公眾觀點的報道。58

更重要的是,《約克公報》是極少數仍然在刊登歐文·拉鐵摩爾(Owen Lattimore)的每週專欄的報紙之一。拉鐵摩爾曾是蔣介石的顧問,但到1947年時,他對國民黨已經非常不滿了。拉鐵摩爾對抗議示威發表了機智狡黠的評論,把某些人的自我欺騙轟得粉碎——這些人自從20世紀早期以來,就把中國學生的抗議歸罪於“外來教唆者”。雖然對示威遊行是針對美國“感到警覺”, 拉鐵摩爾仍然把它們稱作增進中國批評自由的“健康”趨勢。他下結論説,運動“對國務院的行為構成了嚴重警告”。59

於是,除了少數值得注意的例外,美國媒體對強姦案和中國抗議活動的報道,未能解釋為什麼中國學生相信這起案件是如此的重要。中國學生們的聲音一般不會被原貌報道(這是拉鐵摩爾試圖做的),而是透過嚴重過濾的美國視角而呈現。美國媒體在很大程度上錯過了一個解釋問題的機會。這個問題就是馬爾韋納·林賽所説的, 美國大兵作為“美國使者”,可能給美國政策和民間交流理解所帶來的問題。60

1 月17日,對皮爾遜下士的軍事審判在北京開庭。負責審判的,是一個由七名美國軍官組成的小組,他們都是男性。皮爾遜審判的庭辯全文會使大多數讀者確信,強姦的確發生了。61 海軍中校保羅·菲茨傑拉德(Marine Lieutenant Colonel Paul Fitzgerald)以一種嚴肅和避免冒犯的態度,執行了公訴。他質詢了一連串的中國軍隊僱員和警方目擊者;這些證人作證説,他們看見皮爾遜壓在沈崇身上,並聽見沈崇在哭泣。這些證人還説,來自另一個海軍陸戰隊員普里查德的威脅,阻止了他們援助這位年輕的女性。直到中美聯合警所的警員到達之後,他們才能夠把皮爾遜從沈崇身上分開,並逮捕了他。62

對皮爾遜的辯護,包括了隱射沈崇為了錢而同意發生性關係。這一説法在沈崇證明了她從家裏得到了足夠的資助,並願意提供銀行記錄予以證明之後,變得不具説明力。不但如此,有兩位醫生都作證説,沈崇生殖器部位的情況表明她之前很少有或者沒有過性經歷。這兩位醫生包括一位強姦發生幾個小時後,在警察局檢查沈崇的中國醫生,以及一位第二天檢查沈崇的美國軍醫。沈崇陰道口的損傷,儘管相對不嚴重,但和一個婦女被醉漢在低於冰點的夜晚強姦的情形相符合;雖然兩位醫生都承認説,如果沈崇是處女,那麼這種傷害在自願的性行為中也可以發生。63

2014年12月16日,漫畫家丁聰先生的夫人沈峻在北京因病辭世。沈峻正是當事女生沈崇。

在庭辯中,一個更重要的發現,是美軍憲兵在從中國警方手中接手皮爾遜時,未能把警方記錄在案的強姦指控,清楚明白地翻譯成英語。64

而對皮爾遜下士的辯護,則在沈崇沒有做出太多的身體抵抗這一點上大作文章。辯護詞説,如果沈崇不是同意了發生性行為,而是作出抵抗,她的生殖器部位和身體其他部位就會受到更為嚴重的傷害。兩位陸戰隊員也提供證詞説,強姦發生的地區距離一個交通繁忙的大馬路只有65碼; 皮爾遜的辯護律師説,如果沈崇大聲哭喊, 就應該會有人過來救助她。代表皮爾遜的海軍中校約翰·馬斯特斯(Lieutenant Colonel John Masters),一開始試圖把沈崇描繪為性經驗豐富的人,以打擊沈崇的可信度;但在有證據顯示沈崇缺乏性經驗之後,他又試圖把這些證據用來為自己服務, 論證説沈崇的傷正是因為她首次性交沒有經驗而造成的。

在質詢沈崇時,馬斯特斯竭盡全力地要把沈崇誘入供詞前後矛盾的陷阱裏;但在總結陳詞時,他又論證説,沈崇證詞的前後一致性恰恰説明了沈崇編造事實,並預先進行了演練。馬斯特斯最後下結論説:

“被告(皮爾遜)承認發生了性交,但該行為是在雙方都同意的情況下發生的……我們對這一案件的一個方面感到難以理解:為什麼任何人願意呆在那片寒冷不舒服的跑馬場長達三個小時,並且性交兩到三次……這一獨特的情形也許可以歸結於這樣一個事實:關於一個男人和一個女人會做哪些事情,來滿足他們自從人類誕生以來就有的一種原始衝動,我們現在還不能真正理解。”65

菲茲傑拉德代表125磅 的沈崇對6英尺高的皮爾遜提出了控訴。菲茲傑拉德反駁説,“(關於強姦的)法律並未要求一位女性為了表明她對一個男子的性侵犯的反對,做出超過她的年紀、力量、周圍的事實、以及所有伴隨條件所能允許合理的事情”。他接着強調了“同意”和“屈服”在法律上的區別——身體上的抵抗可能會 對女性造成更大的傷害。 菲茲傑拉德在總結陳詞中説道:“我認為被告很難解釋,為什麼一個年輕的、受庇護的中國女孩,出身於上等家庭,卻願意在零下8度的晚上,在一片荒涼的操場上,和一個她隨意認識的醉漢待上三個小時。只有一個符合邏輯的解釋——她留了下來,因為她被迫如此。”67

主持軍事法庭審判的軍官們判定皮爾遜犯有強姦罪,他的共謀犯有襲擊罪。在華北陸戰隊基地的美國大兵們,對皮爾遜被判服刑15年感到憤怒,並開始把此事稱作“華北的德雷福斯案件” 。他們聲稱,皮爾遜是為了平息中國的民族主義抗議示威而被犧牲掉的。68

但審批的最終結果卻在事實上證實了中國學生們對“治外法權”復活的恐懼,因為華盛頓的政府官員很快就推翻了判決結果。雖然駐華海軍陸戰隊的指揮官塞繆爾·霍華德將軍(General Samuel Howard),在1947年2月的一份備忘錄中堅持原有的判決,美國海軍軍法長 O. S. 科爾克拉夫(O. S. Colclough)在1947年6月發佈的一份報告中,表態支持將皮爾遜無罪釋放。在該報告中,科爾克拉夫歪曲了軍事法庭審判中的一些呈堂證供,尤其是沈崇衣裙的情況。

他還系統地淡化了首次遭遇皮爾遜和沈崇的中國軍隊僱員以及警察的證詞,而對皮爾遜喝酒的同伴和後來才抵達現場的美國憲兵們的證詞予以更多的重視。儘管美國海軍審判評論和寬赦委員會在7月份的結論是,“證據足以毋庸置疑地支持法庭關於強姦的指控”,科爾克拉夫的建議最終獲得了勝利。美國海軍執行秘書長約翰·沙利文(John Sullivan)逆轉了有罪判決,並下令將皮爾遜和普里查德從位於加州終端島(Terminal Island)的海軍駐地釋放,送返原部隊繼續服役。時任美國國防部長、總領美國武裝力量的詹姆斯·弗雷斯特爾(James Forrestal),在8月份簽署了將皮爾遜無罪釋放的最終命令,但他的日記(公開的或未公開的)並未直接提及皮爾遜案件。69

對軍事法庭判決的這一逆轉,當然使中國人對美軍及其政策的敵視更甚。事實上,即使是支持國民黨的中國報紙和官員也對判決的翻盤表示了震驚和沮喪。70曾擔任中國駐美大使,並在1947年擔任國立北京大學校長的胡適,對無罪開釋的判決進行了大力抨擊——他此前用他的名譽向學生們擔保軍事法庭的公正性。司徒雷登大使除了將胡適的執着抗議轉交其在美國國務院的上司之外,並無良策;他談到了胡適的抗議的重要性,並補充説,新的裁決“將無疑為反美磨坊提供穀物”。71

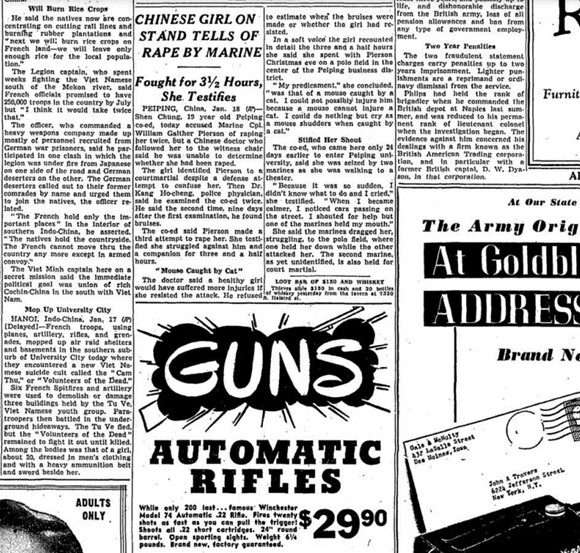

1947年初,《芝加哥論壇報》對沈崇案審判的報道

1946 年12月和1947年1月重新開始的獨立學生運動,不但威脅到了美國在中國的地位,也對戰後的國民黨政府提出了挑戰:國民黨政府進行內戰非常不得人心,更別提在學生和知識分子中間了。事實上,一位北京學生向一個美國領事館官員報告説,抗議主要是針對國民黨,但日益增加的示威“公開針對國民黨而非美國,這可能對許多捲入的學生是致命的”。72

在重慶的抗議示威遭到了嚴厲的鎮壓;根據美國領事館的報告,在有些案例中,警察偽裝成學生和示威者混在一起,隨後毒打他們。這引發了完全針對當地政府而非美國的新抗議。73 另一方面,漢口的美國領事館則聲稱,當地的國民黨政府默許了那裏的示威;領事館的官員們猜測,這是因為中國人民對時局普遍感到不滿,從而可能使得“當地官員歡迎人民的注意力被反美示威所分散”。74

在華的美國官員們注意到了1月份的示威有效地把中國的學生們聯合了起來。751947年2月,作為對強姦的抗議的直接後果,國民黨政府在北京抓捕了數千的學生和知識分子;與此同時,美國領事館官員邁爾·邁爾斯(Myrl Myers)和小詹姆斯·斯皮爾(James Speer II)在電報和文章中對國民黨政府發表了非常嚴厲的批評。

一份海軍陸戰隊的情報備忘錄也注意到,那些上了抓捕黑名單的人,不但包括共產主義分子,還包括那些秘密警察所稱的“危險的自由主義分子”。76 這些逮捕最終標誌着受過教育的城市中國人和政府的最後決裂。逮捕並未阻止學生抗議(這些抗議迅速開始囊括諸多議題),反而幫助把國民黨的所有反對者都推向了中國共產黨一邊,這對蔣政府在1949年的倒台起了推波助瀾的作用。77

中國學生對強姦的激烈反應可以部分被特定的中國國情和傳統所解釋:對中國的“強姦”所引發的該國半殖民地地位的聯想;傳統上學生階層的精英主義;中國學生在 1946-1947年冬天所面臨的嚴峻經濟困境;以及受教育中國人對任何民族的普通士兵的輕蔑,這體現在“好男不當兵,好鐵不打釘”這一説法上。也許我們 還可以補充一條:即使是皮爾遜的辯護律師也在軍事法庭的審判中將之描繪為“沉悶而智力低下”;中國報紙則稱皮爾遜“粗俗”。78

但在分析中國局勢的具體情形時,我們還應記得如下一個貫穿世界歷史的觀念:“強姦”和一個民族的從屬地位之間的聯想,以及對異族士兵或武士作為潛在的或事實上的強姦犯的猜疑。格爾達·勒納(Gerda Lerner)最近論證説,古時候,在戰爭中捕獲並強姦女性標誌着奴役的開始。她對戰爭中強姦的社會涵義給出了一個解釋:“對於被征服者來説,女性被強姦有着雙重影響:強姦羞辱了女性,並象徵着男性的被閹割”。79

聖經舊約《朱迪斯之書》和荷馬的《伊利亞特》都是很好的例子,説明了女性的被綁架和被強姦,以及對此的抗議反抗,在許多社會的創始神話中都佔據了中心位置。尼可羅·馬基雅維利(Niccolo Machiavelli)在16世紀譴責了異國士兵對意大利的“強姦”,他所遣用的詞句也是中國學生們可以很容易借用的。80

當然,抗議“外來者”強姦的男性抗議者們也並非全無問題。對非裔美國人或土著印第安人強姦白人婦女的恐懼,深刻地塑造了美國白人社會和美國白人的種族主義。對強姦的這種恐懼也類似地影響了美國社會在20世紀20、30年代對中國人的形象塑造,以及在20世紀40年代早期對日本人的形象塑造。81 正如我們所看到的那樣,一些自由主義的美國人不情願支持發生在中國的對強姦的抗議,正是因為他們反感於美式思維對跨種族性行為的陳見。82

1946 年發生在北京的強姦,以及最近發生在沖繩的暴行,並不是作為一項軍事政策而被故意慫恿鼓勵的,但它們提醒了我們,士兵們的施暴對象並不侷限於“敵人”或“被征服的”婦女。83然而40年代的中國人和90年代的沖繩人有理由看到在軍事佔領、襲擊婦女、以及侮辱他們的國家之間的聯繫。除了戰爭和征服, 軍事佔領用例子證明了前美國國防部副部長弗雷德·埃克爾(Fred Ikle)一句令人震驚但分外坦率的評論:“軍事生活可能正確地培養了傾向於強姦的態度”。84

即使呼籲對強姦者施予懲罰,中國婦女協會在1947 年也注意到了繼續軍事佔領所涉及到的更廣泛矛盾:“這一事件……反映了美國士兵們在不再有戰爭的情況下,對駐紮於一個陌生國家所感到的厭倦和悲傷”。85 軍事官員、外交官、以及外交關係的歷史學家們忽略了佔領軍士兵們在國家之間所產生的不可避免的緊張關係:正如《紐約時報》在1946年關於日本的頭條報道中富有預見性地所説的那樣,士兵們對當地人民的行為“危及了佔領的使命”。

(譯文完)

譯後記

“《血管》帶有鮮明的第三世界知識分子標記。書中大量引用其他拉美作者的資料、分析和結論,甚至尚未發表的著作;透過其中,我們似乎感到一個具有同樣感受、同等覺悟並互相支持的知識分子羣體。在首次披露的資料處,作者一一註明‘為了寫這一段,我查閲了……’,或者直接敍述自己的大量親歷——我注意到他都是乘坐底層人的長途公共汽車去旅行、訪問的。作者還

引用了不少歐洲、美國學者的原文著作。這種‘我有證據’的話外音使人微微有一點傷感。歐美知識分子不需要這樣做,他們的國籍就是權威。如果他們為受害者説話,那是要人感激涕零的。他們的每一點新發現都屬於赫赫有名的‘新歷史主義’,而受害者的切膚感受從來就令人懷疑。”

——《拉丁美洲:被切開的血管·人的命運,書的命運》 (加萊亞諾, 2001, p. 7)。

這篇譯文的緣起,是謝泳2001年5月18日發表於中國報道週刊的文章《重説沈崇案》。《重説沈崇案》的重心,落在如下幾段話上:

“關於沈崇事件,當時無論是國民黨政府還是民間都認為,中共有意識地參預了這一事件。還有人認為,這一事件本身就是中共有意製造的。當時就有傳言説沈崇是延安派來的人等等。但在沒有確切證據的情況下,我們不能輕易下一個結論。還有一種説法是:‘文化大革命後據中共黨內披露,原來沈崇事件完全是一宗政治陰謀,而美軍士兵強姦北大女生則根本為莫須有罪名。原來沈崇本人為中共地下黨員,她奉命色誘美軍,與他們交朋友,然後製造強姦事件以打擊美軍和國民黨政 府,結果證明相當成功。

據悉沈崇在中共建政後改名換姓進入中共外文出版社工作,已婚,現大陸不少七、八十歲左右的文人名流都知道其人。另一説法是,改了名的沈崇在文革期間被紅衞兵批鬥時揭穿身份,她向紅衞兵承認,她並未遭美軍強姦,之所以這樣説是為了黨的事業。

文革中還有傳言,説沈崇在山西五台山出家,並説有人曾見過等等。這些説法都沒有提出足夠的證據,所以它只能幫助我們在分析沈崇案事多一種歷史視角,如此而已。雖然現在找不到沈崇案是由某一黨派故意製造的證據,但中共有意識地參預和利用了沈崇案,確是事實。”

我個人認為,謝泳的文章有兩個問題。

第一、 有利用含沙射影的方式打擦邊球的嫌疑。文章用“有傳言説”、“有一種説法”、“另一説法”、“文革中有傳言”等方式,於不經意間將污名扣於他人頭上;然後再用“沒有確切證據,我們不能輕易下一個結論”、“所以它只能幫助我們在分析沈崇案時多一種歷史視角,如此而已”這樣貌似公允的語句,試圖將自己撇清。這種用晦暗不明的詞句進行心理暗示的手法,實在談不上光明磊落,更不是誠實做學問的學者態度。

第二、 在引用歷史資料時,故意混淆各事件發生的先後順序,只從某一特定角度和立場引用史料,試圖利用細節的“翔實”,坐實前文對讀者的心理暗示。

使用心理暗示玩曖昧的曲折技巧,西方學界從心理學、大眾傳媒學、公共關係學等各方面都有過系統總結。篇幅所限,我們先略過不提。我只想在此略談一條歷史研究的常識:謝泳那一堆“據説”和“如此而已”貌似公允,實則並未將自己撇清,因為他違反了做歷史研究的基本要求。

歷史研究有一套經過實踐檢驗的方法,這些方法從本科開始就會反覆強調。美國大學大約是在本科三年級的時候開始系統的訓練,其代表作是一本流行的教材:《究根溯源:歷史研究與寫作指南》(Going to the Sources: A Guide to Historical Research and Writing)。

這樣一套系統的歷史研究方法,我們從謝弗教授的學術論文中可見一斑:史料要儘量採用原始資料(論文中引用的美國政府官員的電報、日記等);每一個結論都要反覆推敲,用史料作支持(論文中討論“抗議示威是否是保守勢力重新強調傳統性別關係的努力”);當有互相沖突的史料時,要仔細甄別比較,找出較為可信者(論文中對馬歇爾兩位助手不同看法的比較)。

謝弗教授的論文篇幅不長,但註解就有85條,幾乎每一兩句話就有一條論據支持,正方反方的史料都有顧及。這是史學界所遵循的嚴謹治學方法的一個例子。而細觀謝泳文章,通篇都在引用同一立場的人的話語:這些人説話是在什麼背景之下?有多大的可信度?與他們立場對立的人又是怎麼説的?誰的話更符合實際?這些問題在謝泳的文章裏都沒有體現。所以受過歷史學基本訓練的人,讀了謝泳的文章應該馬上產生一種違和感:文章缺乏立體感,沒有給讀者一副完整的全景圖(panorama)。相比之下,謝弗教授的論文就全面多了。

可能有讀者覺得我小題大作:“怎麼搞得像破案似的?不至於吧?”其實按照正統的治史方法,讀史寫史就應該像破案。西方學者甚至直接以此為名——《事實之後:歷史偵破的藝術》(After the Fact: the Art of Historical Detection) 。

中國作為史書大國,治史的傳統更是嚴謹。歷史學家嚴耕望先生對史料的選取尤其謹慎,他告誡後輩説:

“研究一個問題,在最初剛剛着手的時候,自己可能毫無意見;但到某一階段,甚至剛剛開始不久,自己心中往往已有一個想法,認為事實真相該是如何。此時以後,自不免特別留意與自己意見相契合的證據,也就是能支持自己意見的證據;但切要記着,同時更須注意與自己意見相反的證據。這點極其重要,不能忽略。換言之,要注意關於這個問題的所有各方面的史料,不能只留意有利於自己意見的史料,更不能任意的抽出幾條有利於自己意見的史料。有些問題,史料很豐富,若只留意有利於自己意見的史料,那麼幾乎任何問題都可以照自己意見的方向去證明,這可説是抽樣作證。現在某方面人士利用史學作為政治的工具,為政治服務,他們的主要方法之一就是抽樣作證! ”——嚴耕望:《治史三書·治史經驗談》 (嚴耕望, 1998, pp. 30-31)。

將謝泳的文章和謝弗的論文相比較,誰在抽樣取證,一目瞭然。如果讀者還嫌謝弗教授選取的中國方面的資料太少,不妨細讀陳郢客的文章:《温故知新沈崇案》。

從若干史學前輩的文章,從謝弗教授的這篇小文,我們都可以看到嚴肅的歷史研究與“據説、傳言”毫不相容。為了政治目的而玩弄曖昧,用文學手法代替辛苦嚴肅的考證,末了又用“多一種歷史視角,如此而已”想把自己摘乾淨,多少有些有辱斯文了。

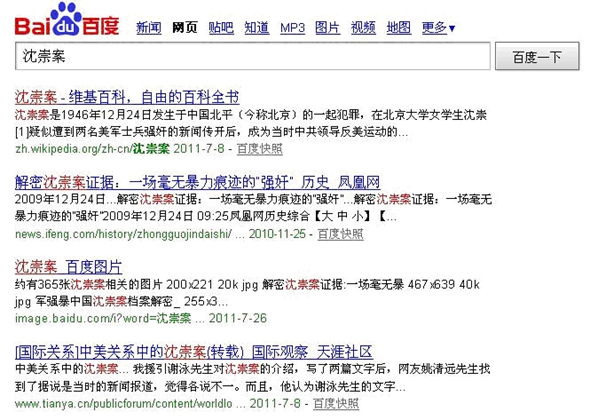

謝泳的《重説沈崇案》出爐10年有餘,影響不小。用百度隨手搜一下,“一場毫無暴力痕跡的‘強姦’”赫然在列(見下圖):

其他難聽的話還包括“奉命被強姦”、“政治仙人跳”、“色誘”,等等,林林總總,不一而足。

人皆有父母兄弟妻女,論身處地,何忍如此?

本文系觀察者網獨家稿件,文章內容純屬作者個人觀點,不代表平台觀點,未經授權,不得轉載,否則將追究法律責任。關注觀察者網微信guanchacn,每日閲讀趣味文章。

(翻頁為尾註)

1 “Beijing,” which means “Northern Capital;” was not the capital of China in the 1930s and 1940s, and was then called “Beiping,” or “Peiping” in the Wade-Giles transliteration. I refer to this city as Beijing for the sake of consistency. I use pinyin transliterations, except when quoting directly from sources transliterated in the Wade-Giles format, although I give both transliterations the first time I refer to Chinese places or names.

2 For a sampling of press coverage of the recent rape and protests in Okinawa, see Andrew Pollack, “Rape Case in Japan Turns Harsh Light on U.S. Military,” New York Times, Sept. 20, 1995; Pollack, “Okinawa Governor Takes On Both Japan and U.S.,” ibid., Oct. 5, 1995; Sheryl WuDunn, “Rage Grows in Okinawa Over U.S. Military Bases,” ibid., Nov. 4, 1995; Nicholas Kristof, “Welcome Mat Is Wearing Thin for G.I.’s in Asia,” ibid., Dec. 3, 1995; “The Women of Japan Again Appeal to the Peace-Loving People of the World,” ibid., April 12, 1996, A25. For documents, in English translation, of the protests of Okinawana women against the rape and against the continued presence of GIs, see Takazato Suzuyo, “Enough is Enough!” AMPO: Japan Asia Quarterly Review, 26 (Sept. 1995), 3-5; “An Appeal for the Recognition of Women’s Human Rights,” ibid., 27 (May 1996), 48. See also Rick Mercier, “Lessons from Okinawa,” ibid., 27 (May 1996), 24-31; Muto Ichiyo, “The LDP’s Election ‘Victory,’” ibid., 27 (Jan. 1997), 2-7; and Nicholas Kristof, “Okinawa Vote Rejects New U.S. Military Base,” New York Times, Dec. 22, 1997. On protests in response to an earlier rape in Okinawa, see “Offenses by GIs Stir Okinawans,” New York Times, June 21, 1970, p. 8, and U.S. Embassy, Tokyo, Political Section, Daily Summary of Japanese Press, Jan. 6, 1971.

Elizabeth Heineman, “The Hour of the Woman: Memories of Germany’s ‘Crisis Years’ and West German National Identity,” American Historical Review,1 01 (1996), 354-395; the special issue of October,72 (Spring 1995) on “Berlin 1945- War and Rape”; Norman Naimark, The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945-1949 (Cambridge, Mass., 1995), chapter 2; Yuki Tanaka, Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II (Boulder, Colo., 1996), chapter 3; Nicoletta Gullace, “Sexual Violence and Family Honor: British Propaganda and International Law During the First World War,” American Historical Review, 102 (1997), 714-747; Cynthia Enloe, Does Khaki Still Become You? The Militarization of Women’s Lives (Berkeley, forthcoming), chapter 4.

On sexual relations more generally between U.S. soldiers and civilian women outside the continental United States, see Petra Goedde, “From Villains to Victims: Fraternization and the Feminization of Germany, 1945-1947,” Diplomatic History, 23 (1999), 1-20; John Willoughby, “The Sexual Behavior of American GIs During the Early Years of the Occupation of Germany,” Journal of Military History, 62 (1998), 155-174; David Reynolds, Rich Relations: The American Occupation of Britain, 1942-1945 (New York, 1995); Sonya Rose, “Sex, Citizenship, and the Nation in World War II Britain,” American Historical Review, 103 (1998), 1147-1176; Beth Bailey and David Farber, The First Strange Place: The Alchemy of Race and Sex in World War II Hawaii (New York, 1992).

On the involvement of U.S. soldiers in a postwar culture of prostitution in Asia, see Saundra Pollock Sturdevant and Brenda Stoltzfus, eds., Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the U.S. Military in Asia (New York, 1993), and Katharine H. S. Moon, Sex Among Allies: Military Prostitution in U.S.-Korea Relations ( New York, 1997).

An investigation of the Chinese protests of 1946-1947 also provides important background for the Chinese nationalist upsurge that followed the NATO bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in the spring of 1999. For one of the better articles in the U.S. mass media on those more recent protests, see Melinda Liu, “Wounded Pride: Rage in Beijing,” Newsweek, 133 (May2 4, 1999), 30-32.

4 Suzanne Pepper, Civil War in China: The Political Struggle, 1945-1949 (Berkeley, 1978), 52-58; Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Student Protests in Twentieth Century China: The View from Shanghai (Stanford, Calif., 1991), 139-142, 261-263; Lincoln Li, Student Nationalism in China, 1924-1949 (Albany, N.Y., 1994), 131-135; Jessie Lutz, “The Chinese Student Movement of 1945-1949″ Journal of Asian Studies, 31 (1971), 89-110; Joseph K. S. Yick, “The Communist-Nationalist Political Struggle in Beijing During the Marshall Mission Period,” in Larry Bland, ed., George C. Marshall’s Mediation Mission to China, December 1945-January 1947 (Lexington, Va., 1998), 357-388; Yick, Making Urban Revolution in China: The CCP-GMD Struggle for Beiping-Tianjin, 1945-1949 (Armonk, N.Y., 1995), esp. 96-102; Zhiguo Yang, “U.S. Marines in Qingdao: Society, Culture, and China’s Civil War 1945-1949,” in Ziaobing Li and Hongshan Li, eds., China and the United States: A New Cold War History (Lanham, Md., 1998); and especially James Cook, “Penetration and Neocolonialism: The Shen Chong Rape Case and the Anti-American Student Movement of 1946-47,” Republican China, 22 (1996), 65-97, but note that Cook rendered the names of the rapist and his accomplice incorrectly. For analyses of recent Chinese publications on these issues, especially through memoirs of participants, see works by Wasserstrom and Yick cited above.

5 For a contemporary pamphlet that analyzed this case, see Thurston Griggs, Americans in China: Some Chinese Views (Washington, D.C., 1948), esp. 7-14, 25-30. For memoirs by U.S. diplomats that discuss it, see John Robinson Beal, Marshall in China (Garden City, N.Y., 1970), 344-346; John F. Melby, The Mandate of Heaven: Record of a Civil War, China 1945-49 (Toronto, 1968); and John Leighton Stuart, Fifty Years in China (New York, 1954), 44-45.

For treatment of postwar Marine Corps activities in China, see Henry Shaw, Jr., The United States Marines in North China, 1945-1949 (Washington, D.C., 1960), and Benis Frank and Henry Shaw, Jr., Victory and Occupation: History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II (5 vols., Washington, D.C., 1968), vol. 5. For the standard overviews of U.S.-China relations during this period, see Michael Schaller, The United States and China in the Twentieth Century (New York, 1990); Warren Cohen, America’s Response to China: An Interpretative History of Sino-American Relations (New York, 1980); Dorothy Borg and Waldo Heinrichs, eds., Uncertain Years: Chinese-American Relations, 1947-1950 (New York, 1980); Tang Tsou, America’s Failure in China, 1941-1950 (Chicago, 1963). For recent historiographical surveys of this period, see the essays by Nancy Bernkopf Tucker and Chen Jian in Warren Cohen, ed., Pacific Passage: The Study of American-East Asian Relations on the Eve of the Twenty-First Century (New York, 1996).

Susan Brownmiller, Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape (New York, 1976), 5, 31, and 23-118 passim. Hazel Carby is cited in Atina Grossman, “A Question of Silence: The Rape of German Women by Occupation Soldiers,” October, 72 (1995), 43-63, at 47. On interconnections between gender, race, and nationalism, see Vicki Ruiz and Ellen DuBois, eds., Unequal Sisters: A Multicultural Reader in U.S. Women’s History (New York, 1994), esp. xi-xvi, and Chandra Talpade Mohanty, “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses,” in Mohanty, Ann Russo, and Lourdes Torres, eds., Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism (Bloomington, 1991), 51-80.

6 Renwick Kennedy, “The Conqueror,” Christian Century, 63 (April 17, 1946), 495-497; see also Oswald Garrison Villard, “Our Military Disgrace Abroad,” Christian Century, 63 (June 26, 1946), 804-806; Albert Jolis, “Were GIs Good Ambassadors?” Common Sense, 15 (Jan. 1946), 28-30; and Ashley Montagu, “Selling America Short,” Saturday Review of Literature (July 26, 1952), 22-23.

7 New York Times, July 14, 1946, p. 1; ibid. (editorial), July 15, 1946, p. 24; “Army Acts to Improve Conduct in Japan,” Christian Century, 63 (Aug. 7, 1946), 956; New York Times, March 6, 1946, p. 7. On sentencing in separate cases of GIs for the rape of Japanese women, see Pacific Stars and Stripes (Tokyo), July 12, 1946, p. 4, and New York Times, Dec. 25, 1946, p. 30. Eichelberger’s earlier order banning GIs from walking on the streets with their arms around Japanese women seems to have been based partly on prudery, partly on a desire to avoid inflaming anti-U.S. sentiment, and partly on the unseemliness to Americans at home of literally embracing our recent enemy; see Eichelberger, memorandum to 8th Army commanders, March 23, 1946, box 433, Records of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, Record Group 331, National Archives, College Park, Md. Tanaka, Hidden Horrors, 103, presents evidence from Japanese sources of mass rape by U.S. soldiers in Okinawa and elsewhere in Japan as the war was ending. For a different view, see the thoughtful comments on GIs, prostitution, and sexual relations in Theodore Cohen, Remaking Japan: The Occupation as New Deal, ed. by Herbert Passin (New York, 1987), 119-136.

Novelist Pearl Buck made the theme of sex and war central to her description of the American occupation army in Japan in The Hidden Flower (New York, 1952). In a passage that anticipated Brownmiller’s analysis, Buck wrote of her main character: “[T]he subjection of a conquered country had changed him as it changes all men. There are men who feel compelled to force conquered women to submit to them, it is the final phase of war, the completion of personal victory” (p. 224); Brownmiller, Against Our Will, 27: “rape is the act of a conqueror.” See also J. Glenn Gray, The Warriors: Reflections on Men in Battle (1959, New York, 1967), 66-67.

8 “GI Welcome Mat Wears Out in China,” Amerasia, 10 (1946), 173-174. For similar comments and concerns, see Melby, The Mandate of Heaven, 229; Pearl Buck, “Our Last Chance in China,” Common Sense, 13 (1944), 265-268; and Harold Isaacs, No Peace With Asia (New York, 1947), chapter 1. For a positive interpretation of the interaction of GIs and the Chinese people, see William Lockwood, “The G.I. in Wartime China,” Far Eastern Survey, 16 (Jan. 15, 1947), 9-11.

9 See “Record of Proceedings of a General Court Martial Convened at Headquarters, Fifth Marines, Peiping, China: Case of William G. Pierson, January 17, 1947” (811.32/1-1748 [sic]), box 5044, General Records of the Department of State, Record Group 59, National Archives, College Park, Md. (hereafter Court Martial, Pierson), and “Marine Faces Life for Rape if Finding Stands,” New York Herald-Tribune, Jan. 23, 1947, p. 24.

10 For an accessible account of the initial student demonstrations, see “Chinese Paraders Ask Marines To Go,” New York Times, Dec. 31, 1946, p. 6. This dispatch quoted a headline in an independent Shanghai newspaper: “What Japanese Troops Did Not Do, American Troops Are Doing.” For translations of early accounts in the Chinese press, see U.S. Embassy, Nanking, Chinese Press Review, #196 (Dec. 31, 1946), 3, and U.S. Consulate, Peiping, Chinese Press Review, #232 (Dec. 31, 1946), 2. See also Jack Belden, China Shakes the World (1949; New York, 1970), 11-13.

11 See Cook, “Penetration and Neocolonialism,” and Dorothy Ko, Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth Century China (Stanford, Calif., 1994), 1-2. For related comments on prostitution and China’s weakness in the international arena, see Gail Hershatter, Dangerous Pleasures: Prostitution and Modernity in Twentieth-Century Shanghai (Berkeley, 1997), 265-267. Imperial Russian and German troops engaged in widespread raping as well as looting in putting down the Boxer Rebellion; see Stuart Creighton Miller, “Ends and Means: Missionary Justification of Force in Nineteenth Century China,” in John King Fairbank, ed., The Missionary Enterprise in China and America (Cambridge, Mass., 1974), 249-282, at 275.

On the prewar identification in the Western mind of Shanghai with sexual licentiousness, prostitution, and the availability of Chinese women for Western soldiers, sailors, and other travelers, see Hershatter, Dangerous Pleasures, 55-56, 234; Frederic Wakeman, Jr., Policing Shanghai, 1927-1937 (Berkeley, 1995), 109-110; and the contemporary source, All About Shanghai and Environs: A Standard Guide Book, Edition 1934-35 (reprint edition, Taipei, 1973), 73-77.

12 Letter, China Weekly Review (Shanghai), Jan. 25, 1947, pp. 207-208; U.S. Consulate, Shanghai, Chinese Press Review, #239 (an. 3, 1947), 5; “Students’ Strike in Protest Against American Marines’ Violent Act…” enclosure to M. S. Myers to J. Leighton Stuart, Jan. 25, 1947 (811.22/1-1547), box 4607, State Department Papers, 1945-1949, RG 59, NA; Hershatter, Dangerous Pleasures, 293-294. See also U.S. Embassy, Nanking, Chinese Press Review, #198 (Jan. 3, 1947), 4.

13 “Students’ Strike in Protest Against American Marines’ Violent Act…” RG 59, NA. On other actions of GIs that caused injury or death to Chinese civilians, see U.S. Consulate, Peiping, Chinese Press Review, #229 (Dec. 27, 1946), 1, 3; #230 (Dec. 28, 1946), 3; #231 (Dec. 30, 1946), 6; and #242 (Jan. 13, 1947), 3. For efforts by the U.S. Marine Corps to reduce such traffic injuries and fatalities, see “Tientsin Safety Drive Underway,” North China Marine (Tientsin), Dec. 14, 1946, p. 1; “Caution Costs Little, Saves Lives,” ibid., Dec. 14, 1946, p. 3; and “Drivers’ Licenses to be Reviewed,” ibid., March 8, 1947, p. 1. On similar problems in the Philippines that complicated U.S. efforts to obtain long-term military bases, see U.S. War Department, Intelligence Review, #38 (Oct. 31, 1946), 17, and #51 (Feb. 6, 1947), 12-13, and William Winter, “Military Bases in the Philippines,” York Gazette, Jan. 2, 1947, p. 17. On a more recent U.S. Marine Corps aircraft “crew error” that caused the death of twenty people in Italy, see New York Times, Feb. 12, 1998, A7, and March 13, 1998, A3.

14 See the mimeographed translations under the title Chinese Press Review prepared by the U.S. Embassy in Nanjing and the consulates in Beijing, Shanghai, and Kunming, from Dec. 26, 1946, to Jan. 20, 1947. See also Frank Tsao, “A Review and Study of the Student Demonstrations,” China Weekly Review, Jan. 18, 1947, p. 194. On the actions of the American professors, see U.S. Consulate, Peiping, Chinese Press Review, #232 (Dec. 31, 1946), 3; #233 (Jan. 2, 1947), 5; and #236 (Jan. 6, 1947), 4.

15 Reported in China Weekly Review, Feb. 22, 1947, p. 323.

16 For a contemporary account, see H. J. Timperley, What War Means: The Japanese Terror in China (London, 1938); see also Iris Chang, The Rape of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust of World War II (New York, 1997).

17 Israel Epstein, The Unfinished Revolution in China (Boston, 1947), 394-395.

18 “Extraterritoriality” was a system, established in the 1840s after the British victory over China in the Opium Wars, in which foreigners accused of crimes in China would not be subject to Chinese law but to foreign courts in the treaty ports. The United States gave up this privilege in a well-publicized wartime treaty with China signed in January 1943, although within a few months a new agreement quietly exempted U.S. military personnel from the treaty’s provisions. See John King Fairbank, The United States and China (Cambridge, Mass., 1983), 167, 337.

19 U.S. Consulate, Peiping, Chinese Press Review, #243 (Jan. 14, 1947), 3, #245 (Jan. 16, 1947), 4, and #246 (Jan. 17, 1947), 3. See also Charles Canning, “Peiping Rape Case Has Deep Social, Political Background,” China Weekly Review, Jan. 11, 1947, p. 166; New York Herald-Tribune, Dec. 30, 1946, p. 3; ibid., Jan. 1. 1947, p. 8, which reported that the accused claimed his sexual relations with the young woman were “on a professional basis”; ibid.,

Jan. 3, 1947, p. 8; U.S. Consulate, Shanghai, Chinese Press Review, #242 (Jan.7 , 1947), 6, in which Hu Shi (Hu Shih) denied such claims.

20 James Speer II, “Memorandum,” Jan. 3, 1947, attachment to Myers to Stuart, Jan. 15, 1947 (811.22/1-1547), box 4607, RG 59, NA. For a contemporary account of GMD Army rapes and sexual harassment of peasant women by landlords, see Belden, China Shakes the World, 155-156. For reports that differentiated between treatment of peasant women by the Red Army from treatment by the GMD, see Belden, 334; Edgar Snow, Red Star Over China (1938; New York, 1968), 259; Helen Foster Snow (Nym Wales), Inside Red China (1939; New York, 1979), 39-40. For a U.S. Marine Corps report from China that noted that “moral standards among Communist troops are exceptionally high” regarding sexual issues, see Ernest Price, “Memorandum for the Commanding General: Communists and Communism in Shantung,” typescript, Nov. 30, 1945, in box 22, World War II Geographical Area Files, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127, National Archives, College Park, Md.

21 U.S. Consulate, Peiping, Chinese Press Review,# 233 (Jan. 2, 1947), 7-8, quotes a professor at Beijing National University, “who had recently returned from America, [and] said that in his opinion, the Americans are less cultured people than the Chinese.” See also T. M. Chao to Stuart, June 26, 1948, in box 23, RG 127, NA, for complaints about marines occupying the National University of Shandong.

22 “Rape Cases and Rape Cases” China Weekly Review, June 28, 1947, pp. 103-104. On the relationship between chastity and rape in imperial China, see Vivien Ng, “Ideology and Sexuality: Rape Laws in Qing China,” Journal of Asian Studies, 46 (1987), 57-70.

23 Cynthia Enloe, “Spoils of War,” Ms., 6 (March-April 1996), 15; V. Spike Peterson and Anne Sisson Runyan, Global Gender Issues (Boulder, Colo., 1993), 132ff.; Katha Pollitt, “Cultural Rights and Wrongs: Whose Culture?” Boston Review (Oct.- Nov. 1997), 29. For a case study of these ideas in the Chinese context, see Gael Graham, “The ‘Cumberland’ Incident of 1928: Gender, Nationalism, and Social Change in American Mission Schools in China” Journal of Women’s History, 6 (1994), 35-61.

24 Ma Yinchu (Ma Yin-chu), “The People Demand Immediate Withdrawal of U.S. Troops,” China Digest (Hong Kong), 1 (Jan. 28, 1947), 10.

25 U.S. Consulate, Shanghai, Chinese Press Review, #242 (Jan. 6, 1947), 9, and #239 (Jan. 3, 1947), 5; “Chinese Paraders Ask Marines To Go,” New York Times, Dec. 31, 1946, p. 6; Far East Spotlight, 2 (March 1947), 8.

26 See, e.g., Townsend Hoopes and Douglas Brinkley, Driven Patriot: The Life and Times of James Forrestal (New York, 1992), 304-309, and Secretary of War Robert Patterson to Dean Acheson, Dec. 17, 1946 (893.00/12-1746), microfilm LM069, reel 4, RG 59, NA. Of course, the positions of the War, Navy, and State departments were by no means static in these years. General Joseph Stilwell had major differences with Jiang that had led to his recall in October 1944, and he opposed continued military aid to Jiang after the war with Japan ended, while Ambassador Patrick Hurley had strongly backed military aid to Jiang against the CCP until his resignation in November 1945; see Michael Schaller, The U.S. Crusade in China, 1938-1945 (New York, 1979), 173-174, 286-288, 300.

27 Robert Streeper to William Uphouse, Dec. 17, 1946, copy, enclosure no. 2 in dispatch, W. Walton Butterworth to Secretary of State, Jan. 10, 1947 (811.22/ 1-1047), box 4607, RG 59, NA. Of course, some U.S. military officials were also concerned about prostitution’s impact on the venereal disease rate of American soldiers and sailors; see Lt. Gen. Louis Woods, Oral History Transcript, 318-319, U.S. Marine Corps Historical Center, Washington (D.C.) Navy Yard; and Hershatter, Dangerous Pleasures, 301.

28 A. D. Cereghino, memoranda, Jan. 6, 1947, and Jan. 10, 1947, box 23, World War II Geographical Area Files, RG 127, NA.

29 “Marine Corps, Army in China to Be, Withdrawn,” North China Marine, Feb. 1, 1947, p. 1; “Peiping Sees Students in Mass Protest,” ibid., March 22, 1947, p. 3; “Scoops and Salty,” ibid., Feb. 1, 1947, p. 5, and Feb. 15, 1947, p.. 5; William Summers, “The Chaplain Speaks,” ibid., Jan. 25, 1947, p. 8.

30Myers to Stuart, Jan. 15, 1947 (811.22/1-1547), box 4607, RG 59, NA. A U.S. Army official made a strikingly similar comment to Brownmiller twenty-six years later. No matter what information he gave her on GI rapes in Vietnam, he said, “some people will say the Army is a bunch of criminals and the rest will say we run kangaroo courts”; see Brownmiller, Against Our Will, 102.

31 Stuart to Secretary of State, April 22, 1947, U.S. Dept. of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1947 (8 vols., Washington, D.C., 1971-1973), 7: 105-107. Stuart had earlier been president of Yanjing University, whose students actively participated in the demonstrations.

32 Compare Myers to Secretary of State, Dec. 29, 1946, and two telegrams of Dec. 30, 1946, Foreign Relations, 1947, 7: 1-4. Dagong Bao lampooned the “panic” that the incident unleashed in the U.S. Consulate in Beijing, with frantic efforts by radio listening posts to detect broadcasts from the CCP directing the protests; see U.S. Consulate, Peiping, Chinese Press Review, #233 (Jan. 2, 1947), 6.

33See especially Stuart to Secretary of State, Jan. 8, 1947, Foreign Relations, 1947, 7: 13-15, and Butterworth to Secretary of State, Jan. 9, 1947 (893.00/1-947), microfilm LM069, reel 5, RG 59, NA. While couched in more moderate language, some of the consular reports tended to agree with Charles Canning, who in the China Weekly Review, Jan. 11, 1947, pp. 166-167, argued that the CCP was not so powerful “that they were able to ‘instigate’ in a few days a nation-wide mass movement, which had the participation and backing of the majority of Chinese students and intellectuals.”

34 Secretary of State to Stuart, Jan. 4, 1947, and Stuart to Secretary of State, Jan. 8, 1947, in Foreign Relations, 1947, 7: 5-6 and 7: 12-15; see also Stuart to Secretary of State, Dec. 17, 1946 (893.00/12-1746), and Dec. 19, 1946 (893.00/12- 1946), microfilm LM069, reel 4, RG 59; U.S. War Department, Intelligence Review, #47 (Jan. 9, 1947), 13-15. The CCP did, in fact, laud the student demonstrations; see Stuart to Secretary of State, Jan. 16, 1947 (893.00/1-1647), and Jan. 21, 1947 (893.00/1-2147), microfilm LM069, reel 5, RG 59, NA; and U.S. Consulate,

Peiping, Chinese Press Review, #239 (Jan. 9, 1947), 7. Yick, Making Urban Revolution in China, 96-102, emphasizes the leadership of communist urban underground students in this movement.

35“American Officials View Demonstrations Lightly,” Pacific Stars and Stripes, Jan. 4, 1947, p. 4; “Soong Orders Demonstrations in China Halted,” New York Herald-Tribune, Jan. 5, 1947, p. 6; Secretary of State (Byrnes) to Stuart, Jan. 4, 1947, Stuart to Secretary of State, Jan. 8, 1947, both in Foreign Relations, 1947, 7: 5-6 and 7:12-15.

36 On the history of student protests in China, see Wasserstrom, Student Protests in Twentieth Century China; Vera Schwarcz, The Chinese Enlightenment: Intellectuals and the Legacy of the May Fourth Movement of 1919 (Berkeley, 1986); and Hans Schmidt, “Democracy for China: American Propaganda and the May Fourth Movement,” Diplomatic History, 22 (1998), 1-28. For a first-person account of the 1935 anti-Japanese protests, see Helen Foster Snow, My China Years (New York, 1984), 160-164. For contemporary accounts of student activities and attitudes in the post-war years, see Robert Payne, China Awake (New York, 1947), esp. 199-280, and Derk Bodde, Peking Diary, 1948-1949: A Year of Revolution (1950; New York, 1967), esp. 55-57. For two of the many comparisons in the Chinese press between the 1946-1947 protests and previous student activities, see U.S. Consulate, Peiping, Chinese Press Review, #238 (Jan. 8, 1947), 5, and U.S. Consulate, Shanghai, Chinese Press Review, #258 (Jan. 29, 1947), 5.

37 See “Statement by President Truman on United States Policy Toward China, December 18, 1946,” and “Personal Statement by the Special Representative of the President (Marshall), January 7, 1947,” both in Lyman Van Slyke, ed., The China White Paper, August 1949 (1949; 2 vols., Stanford, Calif., 1967), 2: 686-694. On Chinese press reaction to Truman’s speech, see Stuart to Secretary of State, Dec. 23, 1946 (893.00/12-2346), microfilm LM069, reel 4, RG 59, NA.

38 U.S. Consulate, Shanghai, Chinese Press Review, #244 (Jan. 9, 1947), 7; see also ibid., #243 (an. 8, 1947), 6. An early overview of U.S. policy in China agreed that the rape case influenced Marshall; see Griggs, Americans in China, 14, 25-30.

“Press Release Issued by the Department of State, January 29, 1947,” China White Paper, 2: 695. Some American conservatives in Congress, who undoubtedly interpreted Marshall’s abandonment of his mission in the context of this Chinese movement against the presence of U.S. troops, and who feared that his statement presaged continued

military pullout, called for the United States to keep its soldiers in China; see the Washington Post, Jan. 12, 1947, p. 5M.

39 Stuart to Secretary of State, Jan. 2, 1947, Foreign Relations, 1947, 7: 4-5; United Press dispatch, Washington Post, Jan. 4, 1947, p. 5. Forrest Pogue, in George C. Marshall: Statesman, 1945-1949 (New York, 1987), 137, states that Marshall, confronted by demonstrators, asked for an interpreter so that he could talk with them. When the interpreter, a U.S. marine in uniform, appeared, Marshall reportedly fumed, “What are you thinking about, getting a Marine up here to be an interpreter for an anti-Marine demonstration?” Unfortunately, neither of the footnotes Pogue supplies discuss the incident in this fashion.

40 See “Personal Statement by the Special Representative of the President, January 7, 1947,” China White Paper, 1: 686-689. For a typical U.S. press account of Marshall’s return, see New York Times, Jan. 12, 1947, sec. 4, p. 2; for one account in which Marshall commented on the demonstrations and refused to blame the CCP for instigating them, see Pacific Stars and Stripes, Jan. 13, 1947, p. 4.

41 See especially Gold telegrams #1902 (Jan. 4, 1947), #1924 (Jan. 10, 1947), and #1962 (an. 20, 1947), and Ming telegram #115 (Jan. 14, 1947), George Marshall Archives, George Marshall Research Foundation, Lexington, Va. For selections, see Dennis Merrill, ed., Documentary History of the Truman Presidency, Volume 6: The Chinese Civil War: General George C. Marshall’s Mission to China, 1945-1947 (7 vols., Bethesda, Md., 1995), especially Gold telegrams #1804 (Nov. 23, 1946), 306, and #1891 (Dec. 28, 1946), 335-338. See also “Marine Corps, Army in China to Be Withdrawn,” North China Marine, Feb. 1, 1947, p. 1.

42 See also Dean Acheson to Truman, July 30, 1949, in China White Paper, 1: xvi, that one reason the United States did not commit large numbers of ground forces to the civil war against the Chinese communists was that “Intervention of such a scope and magnitude would have been resented by the mass of the Chinese people.”

43“China: Nasty Words” Newsweek,29 (Jan. 13, 1947), 40-42; see also Pacific Stars and Stripes (Tokyo), Jan. 20, 1947, p. 2, on departing Marines who said that the Chinese people gave them a “hearty send-off.” One Marine Corps

commander later recalled that the GIs in North China “didn’t know why they were out there,” and “they all wanted to go home-the officers and the men.” See Woods, Oral History Transcript, 318-319.

44 “Anti-American Cries Heard in China as 1947 Arrives,” Washington Post, Jan. 1, 1947, p. 4; “Students Blamed: Chinese Beat U.S. Officer in Shanghai,”ibid., Jan. 2, 1947, p. 3; “Students Demand Yanks Leave China,” ibid., Jan. 4, 1947, p. 5. In several newspapers the “beating” of the American (he was struck several times with his own cane) was the first mention at all of the case and the demonstrations; see “Officer Beaten, Anti-U.S. Feeling Grows in China,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Jan. 2, 1947, p. 10A; “China Students Beat Americans,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, Jan. 2, 1947, p. 1.

45 “National Virility,” Washington Post, Dec. 22, 1946, p. 4B, but see response by “Outraged Veteran,” ibid., Dec. 27, 1946, p. 6; Malvina Lindsay, “American Emissaries,” ibid., Jan. 9, 1947, p. 10. For an analysis of Cold War ideology that notes this perceived crisis of virility, see Geoffrey Smith, “National Security and Personal Isolation: Sex, Gender, and Disease in the Cold-War U.S.” International History Review, 14 (1992), 307-337.

The resolutely anti-CCP Washington Post also editorialized against military aid to Jiang; see “China’s Constitution,” Washington Post, Jan. 5, 1947, p. 4B; “Marshall’s Statement,” ibid., Jan. 9, 1947, p. 10; “China Mission,” ibid., Jan. 30, 1947, p. 6.

46 “Chinese Students Beat U.S. Officer,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan. 2, 1947, p. 8; “Chinese Repeat U.S. Protest,” ibid., Jan. 3, 1947, p. 6; “Chinese Students Oppose Marines,” Christian Science Monitor, Jan. 2, 1947, p. 13; Ronald Stead, “Marshall Exit Tests China Factions,” ibid., Jan. 7, 1947, p. 12; “China Student Marchers Call Yanks Beasts,” Los Angeles Times, Dec. 31, 1946, p. 5; “Chinese Students Intensify Rallies Against U.S. Troops,” ibid., Jan. 4, 1947, p. 1; Polyzoides, “Chinese Student Riots Against U.S. Shocking,” ibid., Jan. 3, 1947, p. 4. Ironically, “Inflammable China,” Christian Science Monitor, Jan. 3, 1947, p. 18, was among the U.S. editorials most sympathetic to the students, and “U.S. Under Fire As China Gets New Constitution,” Los Angeles Times, Jan. 1, 1947, p. 4, was one of the more historically informed analyses of the protests. But the unwillingness to print the word “rape” blunted the impact of such coverage.

47 “Chinese Reds Blamed for Anti-U.S. Wave,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Jan. 4, 1947, p. 5; “Chinese Students Unite to Fight Anti-U.S. Feeling in Colleges,” Washington Post, Jan. 5, 1947, p. 9M; “China Prohibits Demonstrations,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, Jan. 5, 1947, p. 1. The first article here gave no evidence to back up the headline and included misleading statements that stemmed from the refusal to acknowledge that the incident was based on the charge of rape. See also the coverage in Pacific Stars and Stripes, which gave extensive and fairly accurate coverage, but which on Jan. 4, 1947, at 4, predicted that the protests would soon subside, on Jan. 5, at 4, retracted that claim in the face of larger protests, and on Jan. 6, at 4, exaggerated the importance of the pro-American Chinese student faction.

48 “China: Nasty Words,” Newsweek, 29 (Jan. 13, 1947), 40-42; “Chinese Beat Yank; Try to Disrobe Girl,” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 2, 1947, p. 1; William Henry Chamberlain, “Post War Ironies,” Wall Street Journal, Jan. 14, 1947, p. 4; Chamberlain, “Foreign Affairs in Review,” ibid., Jan. 3, 1947, p. 6. Chamberlain insinuated that Chinese anti-Americanism was one legacy of Japanese wartime antiwhite propaganda.

49 “China: New Constitution,” Time, 49 (Jan. 6, 1947), 30, 33; “Painful Surprise,” Time, 49 (an. 13, 1947), 28; see also “Foreign Relations,” Time, 49 (Feb. 10, 1947), 22-23.

50 On Henry Luce’s “paternalism” regarding China, see also T. Christopher Jespersen, American Images of China, 1931-1949 (Stanford, Calif., 1996); on his China policy more generally, see Robert Herzstein, Henry R. Luce: A Political Portrait (NewYork, 1994) and Thomas Griffith, Harry and Teddy: The Turbulent Friendship of Press Lord Henry R Luce and His Favorite Reporter, Theodore H . White ( New York, 1995).

51 See Henry Lieberman in the New York Times, Jan. 2, 1947, p. 11, and Archibald Steele in the New York Herald-Tribune, Dec. 29, 1946, p. 15, and Dec. 30, 1946, p. 3.

52“Chinese Students Again Assail U.S.,” New York Times, Jan. 1, 1947, p. 15; Archibald Steele, “Reds in China Reach a Climax in Abuse of U.S.,” New York Herald-Tribune, Jan. 6, 1947, p. 9. See also Steele, “Marine Faces Life for Rape if Finding Stands,” ibid., Jan. 23, 1947, p. 24, in which he summarized his analysis: “The Christmas Eve affair has done more than any other incident to stir up Chinese resentment against the presence of American troops in China. It was ready-made for the Communists and other groups who have been demanding American withdrawal from China, and they have exploited it to the utmost.” On Steele more generally, see Stephen MacKinnon and Oris Friesen, eds., China Reporting (Berkeley, 1987).

53Whether the sexual double entendre of the New York Herald-Tribune Jan. 6 headline was intentional is impossible to say, but such linguistic excesses in the U.S. press on this case did not correlate with political viewpoints. The New York Times, Jan. 19, 1947, sec. 1, p. 44, described certain court martial testimony as the “climax” of the case, while the Communist Daily Worker, Dec. 30, 1946, p. 2, proclaimed that “Chinese Students, Aroused by Rape, Demonstrate for U.S. Troop Withdrawal.” On gendered discourse in the Cold War, see Frank Costigliola, “The Nuclear Family: Tropes of Gender and Pathology in the Western Alliance,” Diplomatic History, 21 (1997), 163-183; for responses, consult the H-Diplo internet site at http://www.h-net2.msu.edu/-diplo/Costiglioga/htm.

54“Chinese Student Protests,” New York Herald-Tribune, Jan. 4, 1947, p. 12.

55See, e.g., “Furious Peiping Demands U.S. Get Out of China,” Daily Worker, Dec. 31, 1946, p. 2; “‘Anti-American?’ Says Who?” ibid., Jan. 2, 1947, p. 7; “Chinese Students Take Protest to U.S. Envoy,” ibid., Jan. 4, 1947, p. 12; “Bare Third-Degree of Raped Chinese Co-Ed,” ibid., Jan. 22, 1947, p. 2. The leftist U.S. Committee for a Democratic Far Eastern Policy, while attentive to events in China, did not highlight the rape or these protests; see Far East Spotlight, 2 (Feb. 1947), 8, and 2 (March 1947), 8.

Jennings Perry, “Stranger Than Fiction,” PM, Jan. 1, 1947, p. 24. For a sampling of news coverage of the case in PM, see “Peiping Sore at U.S. Marine,” Dec. 30, 1946, p. 8; “Chinese Protests Against GIs Go On,” Jan. 5, 1947, p. 9; “Foreign Round-Up,” Jan. 6, 1947, p. 8. On the impact of the Scottsboro case, see Brownmiller, Against Our Will, chapter 7, and James Goodman, Stories of Scottsboro (New York, 1994).

Some Chinese at the time also connected the Pierson rape to interracial sexual relations in the United States, but in different ways. Economist Ma Yinchu noted in a speech to the Chinese Writers’ League that American blacks would be hanged or burned for raping a white woman, and he asked rhetorically what punishment the GI in this case would receive; see U.S. Consulate, Peiping, Chinese Press Review, #232 (Dec. 31, 1946), 3-4. Randall Gould, the

American editor of the Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury, was quoted in Time, 49 (Feb. 10, 1947), 22-23, as saying “We are beginning to understand what our minorities in the States feel like 24 hours a day.”

57 James White, “Suppose You Are a Chinese Student…” PM, Jan. 2, 1947, p. 6. (None of the other newspapers among the dozen that I surveyed published this AP story.) For a similar analysis, see Epstein, The Unfinished Revolution in China, 396. The phrase “jeep girls” is from 56 “Chinese Students Again Assail U.S.,” New York Times, Jan. 1, 1947, p. 15. For a visual representation of a “jeep girl” from an American military source, see the cartoon by Machin in North China Marine, Dec. 14, 1946, p. 3. For a Chinese editorial asserting that China bore part of the blame because of the “inglorious women” who associated with GIs, see U.S. Consulate, Peiping, Chinese Press Review, #236 (Jan. 6, 1947), 2.

Letters, PM, Jan. 8, 1947, p. 21.

58 “Chinese Students Ask U.S. Troops Quit Country,” York (Pennsylvania) Gazette, Jan. 2, 1947, p. 2; “China Students Beat Americans,” Los Angeles Times, Jan. 2, 1947, p. 7; “Chinese Students Call on U.S. Envoy to Discuss Uproar,” York Gazette, Jan. 4, 1947, pp. 1, 28.

59 Owen Lattimore, “Students Are China’s Hope,” ibid., Jan. 11, 1947, p. 15. On Lattimore’s career, see Robert P. Newman, Owen Lattimore and the “Loss” of China (Berkeley, 1992).

Lindsay, “American Emissaries.”

60 Court Martial, Pierson; “Marine Faces Life for Rape if Finding Stands,” New York Herald-Tribune, Jan. 23, 1947, p. 24. See Cook, “Penetration and Neocolonialism” for the initial Chinese police reports on the case.

Court Martial, Pierson, 4-25 and passim.

61 Ibid., esp. 39, 54, 58, 89-93. The prosecution’s case was weakened by a report by the Chinese doctor that minimized Shen’s injuries. Many Chinese believed that GMD pressure, exerted to avoid conflict with the U.S., was responsible; see a statement from the China Daily News

62 quoted in Daily Worker, Jan. 22, 1947, p. 2, and U.S. Consulate, Peiping, Chinese Press Review, #410 (Aug. 14, 1947), 3. For alleged mistreatment of Shen while being questioned by the Chinese police,

63 see U.S. Consulate, Peiping, Chinese Press Review, #238 (Jan. 8, 1947), 5, but for Hu Shi’s denial of such charges, see ibid., #237 (Jan. 7, 1947),

64 3.Court Martial, Pierson, 32-36, 82-84.

65 Ibid., 62-70 and J1-J5. Key items of contention, as in the more recent O. J. Simpson trial and in the Bill Clinton-Monica Lewinsky case, respectively, were a “bloody glove” and a stained dress. The defense contended that the glove was bloodied when Pierson, on a four-hour drinking bout just prior to the incident, cut his hand on a liquor bottle; see ibid., 14, 79-80, and Exhibit 2. The stained dress was taken as evidence by the police before the trial and, incredibly, was introduced at the trial with holes cut out where the stains had been; see ibid., 100, and Exhibit 7.

【譯文】皮爾遜的審判記錄,第62-70頁,以及J1-J5。類似於最近的辛普森審判和比爾•克林頓—莫妮卡•萊温斯基案件,爭論的關鍵證物有兩件:一副 “血手套”和一件帶污漬的衣裙。辯詞爭辯説,皮爾遜喝了四個小時的酒,然後就在案件發生前,手被一個酒瓶子割傷了,手套上的血就是這麼來的;參見皮爾遜的 審判記錄,第14頁,第79-80頁,以及證物2。帶污漬的衣裙在審判前被警方當作證物拿走,但令人難以置信的是,當這件衣裙在審判中被拿出來的時候,有污漬的地方被剪掉了;參見皮爾遜的審判記錄,第100頁,以及證物7。

66 Ibid., 12-13. One difficulty for Shen was that at least eight Chinese army employees witnessed the rape, but all claimed to have been deterred from acting by threats from Pritchard, Pierson’s accomplice. Fitzgerald argued with some plausibility, at ibid., K2, that Chinese culture did not encourage people to “interfere in the affairs of others” not of their family. He might have argued, but did not, that the Chinese army command would have looked unfavorably on its members confronting an American soldier.

67 Ibid., K1-K2 (emphasis in original). Masters had charged, at ibid., J2, that the fact that Shen kept her heavy gloves on throughout the sexual encounter demonstrated consent, since removing them would have allowed her to scratch Pierson. Fitzgerald responded, at ibid., K2: “[H]ad the girl consented to the intercourse, she would have removed her gloves to assist him and the fact that she kept them on shows she did not want to assist him.”

68 Ibid., 102-103, and addendum (memorandum from Gen. Samuel Howard, Feb. 21, 1947); on Pritchard’s court martial, see “Marine is Convicted Of Peiping Assault,” New York Times, Feb. 1, 1947, p. 6. On GI response, see “Guilty Verdict Displeases EM [Enlisted Men] in Peiping Area” Pacific Stars and Stripes, Jan. 24, 1947, p. 1.

69 O. S. Colclough, “Pierson, William G.,” June 6, 1947, and attached memorandum from John Sullivan, July 3, 1947 (811.32/1-1748), box 5044, RG 59, NA; Howard, memorandum, Feb. 21, 1947, R. H. Cruzen to Acting Secretary of the Navy, July 8, 1947, and memorandum from SECNAV (JAG) [Sullivan] to CO NDB Terminal Island, Calif., Aug. 11, 1947, all in Pierson file, docket #47-156116F, Office of the Judge Advocate General, Department of the Navy, Washington (D.C.) Navy Yard. See also “Service Men Exonerated,” New York Times, Aug. 12, 1947, p. 5. Forrestal had lunch on July 3, 1947-the same day as Sullivan’s first memo reversing the conviction-with Howard, who in February had sustained the verdict, but whether the two men spoke about the case cannot be determined; see James Forrestal Diaries (7 vols., typescript), Seeley G. Mudd Library, Princeton University, 6, 7: 1709, and Walter Millis, ed., The Forrestal Diaries (New York, 1951), 289. Pierson’s Congressional representative from South Carolina, John Riley, had also made inquiries about the case, but the impact of those inquiries on the reversal of the verdict cannot be determined; see Helen Lamberson, memorandum, March 31, 1947, in Pierson file, Washington Navy Yard.

70 Available Navy Department records for the year ending June 30, 1946, indicate that it was not unusual for court martial sentences for rape to be reduced by the Judge Advocate General or by the General Court Martial Sentence Review Board, but overturning convictions for rape was uncommon. Sentences for assault with intent to rape were frequently reduced on review, with intoxication of the assailant often given as a reason for such reduction. See “General Court Martial Sentence Review Board, Interim Report, for period ending 30 June 1946,” esp. 36-38, and “General Court Martial Sentence Review Board, 19 Sept. 1946,” esp. 53-55, both in box 64, Records of Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, Records of the Department of the Navy, Record Group 80, National Archives, College Park, Md.

71 See U.S. Consulate, Peiping, Chinese Press Review, #410 (Aug. 14, 1947), 3; ibid., #411 (Aug. 15, 1947), 3; ibid., #412 (Aug. 18, 1947), 3; U.S. Consulate, Shanghai, Chinese Press Review, #423 (Aug. 13, 1947), 4; ibid., #424 (Aug. 14, 1947), 5.

See Stuart to Secretary of State, June 21, 1947 (811.32/6-2147), June 22, 1947 (811.32/6-2247), June 24, 1947 (811.32/6-2447), box 4662, RG 59, NA. See also the protest by the Committee for a Democratic Far Eastern Policy: ‘Justice For All?” Far East Spotlight, 2 (July 1947), 4.

72 Speer II, “Memorandum,” Jan. 3, 1947. See also Stuart to Secretary of State, Jan. 8, 1947, Foreign Relations, 1947, 7: 13-15: “Embassy considers that, on the whole, demonstrations may best be interpreted as a manifestation of general discontent and unrest caused by overall political-economic situation existing in China.” The resentment against the Chinese government “which cannot be openly expressed is being turned almost entirely against the U.S.”

73Stuart to Secretary of State, Feb. 12, 1947 (893.00/2-1247) and Feb. 15, 1947 (893.00/2-1547), including cables from Consul-General Streeper, in microfilm LM069, reel 5, RG 59, NA.

74Stuart (paraphrasing Krentz) to Secretary of State, Jan. 10, 1947 (893.00/1-1047), ibid.

75Paul Meyer and Fern Cavender, U.S. Consulate, Shanghai, “Memorandum,” June 7, 1947 (893.00/6-1847), ibid., reel 7.

76Myers to Stuart, Feb. 20, 1947 (893.00/2-2047), ibid., reel 5; James Speer II, “Liquidation of Chinese Liberals,” Far Eastern Survey, July 23, 1947, pp. 160-162; Col. George McHenry and J. A. McNeil, Intelligence Memorandum No. 58 (March 10, 1947), in box 22, World War II Geographical Area Files, RG 127, NA.

77See Pepper, Civil War in China, and Yick, Making Urban Revolution in China.

78On the Chinese aphorism about soldiers, see Edwin Moise, Modern China: A History (New York, 1994), 32; see also Court Martial, Pierson, 105, and U.S. Consulate, Shanghai, Chinese Press Review, #253 (Jan. 20, 1947), 7-9.

79Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Patriarchy (New York, 1986), 76-80.

80Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince, trans. David Wootton (Indianapolis, 1995), 42.

81 The literature on the myth of the black rapist is voluminous; see, e.g., Joel Williamson, A Rage for Order: Black-White Relations in the American South Since Emancipation (New York, 1986), and Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, Revolt Against Lynching: Jessie Daniel Ames and the Women’s Campaign Against Lynching (New York, 1979). On the racist use of such charges by Germans after World War I and the impact on U.S. foreign policy, see William Keylor, “‘How They Advertised France’: The French Propaganda Campaign in the United States During the Breakup of the Franco-American Entente, 1918-1923,” Diplomatic History, 17 (1993), 351-373, esp. 369- 371. On the myth of Native Americans as rapists, see James Axtell, “The White Indians of Colonial America,” in Axtell, The European and the Indian: Essays in the Ethnohistory of Colonial North America (New York, 1981), 181-182; William Truettner, ed., The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier 1820-1920 (Washington, D.C., 1991), 162-165; Susan Jeffords, “Protection Racket,” Women’s Review of Books, 8 (July 1991), 10; Annette Kolodny, “Among the Indians: The Uses of Captivity,” New York Times Book Review, Jan. 31, 1993, pp. 1, 26-29.

82 On American perceptions of Chinese as rapists of white women, see John B. Powell, My Twenty-Five years in China (New York, 1945), 156-157, and the film Shanghai Express (1932), discussed in Jonathan Spence, “Shanghai Express,” in Mark Carnes, ed., Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies (New York, 1995), 208-211. On the representation of Japanese troops as a sexual threat to white women, see John Dower, War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (New York 1986), esp. 189, and Tanaka, Hidden Horrors, chapter 3.

Perry, “Stranger Than Fiction.”

83 On the varied forms and purposes of military rape, see Enloe, Does Khaki Become You? and Tanaka, Hidden Horrors, 105-109.

84 Quoted in Richard Raynor, “The Warrior Besieged,” New York Times Magazine, June 22, 1997, pp. 24-29, at 29, emphasis in original.

85 U.S. Consulate, Peiping, China Press Review, #236 (Jan. 6, 1947), 4. For statements by U.S. officials indicating the desire of U.S. soldiers in Asia to return home after World War II, see Forrestal Diaries, April 25, 1947, 7: 1593, Mudd Library; and Rep. Mike Mansfield to Harry Truman, Nov. 7, 1945, Harry S. Truman Papers, Official File, Truman Library, Independence, Mo. See also the later comments of a U.S. Army official that “There is more rape during an occupation because soldiers have more time on their hands,” quoted in Brownmiller, Against Our Will, 78.