達卡平紋細布:沒人知道如何織造的古老布料_風聞

龙腾网-2021-04-25 17:21

【來源龍騰網】

正文原創翻譯:

Nearly 200 years ago, Dhaka muslin was the most valuable fabric on the planet. Then it was lost altogether. How did this happen? And can we bring it back?

大約200年前,達卡平紋細布是世界上最珍貴的布料。後來徹底消失了,為什麼會這樣?我們能夠復原這種布料嗎?

In late 18th-Century Europe, a new fashion led to an international scandal. In fact, an entire social class was accused of appearing in public naked.

在18世紀末的歐洲,一種新服飾引發了國際醜聞。事實上,整個社會階層被指責裸體在公眾場合露面。

The culprit was Dhaka muslin, a precious fabric imported from the city of the same name in what is now Bangladesh, then in Bengal. It was not like the muslin of today. Made via an elaborate, 16-step process with a rare cotton that only grew along the banks of the holy Meghna river, the cloth was considered one of the great treasures of the age. It had a truly global patronage, stretching back thousands of years – deemed worthy of clothing statues of goddesses in ancient Greece, countless emperors from distant lands, and generations of local Mughal royalty.

罪魁禍首是達卡平紋細布,這種珍貴的布料進口自同名城市孟加拉,即當今的孟加拉國。它使用一種稀有棉花,通過16道工序精製而成,這種棉花只生長在神聖的梅格納河兩岸。當時人們將這種布料視為瑰寶之一,風靡全球數千年——人們認為這種布料配得上古希臘的女神像、遙遠國度不計其數的帝王、本土莫卧兒王朝的皇室成員享用。

There were many different types, but the finest were honoured with evocative names conjured up by imperial poets, such as “baft-hawa”, literally “woven air”. These high-end muslins were said to be as light and soft as the wind. According to one traveller, they were so fluid you could pull a bolt – a length of 300ft, or 91m – through the centre of a ring. Another wrote that you could fit a piece of 60ft, or 18m, into a pocket snuff box.

這種布料分為許多種,但最上乘的布料被帝國詩人賦予動聽的名字,例如:“baft-hawa”,字面意思是“空氣織物”,據説這種高檔布料像風一樣輕薄柔軟。一名旅行者這樣描述:它們是如此絲滑,以至於可以拉拽一匹布——長300英尺或91米——穿過一枚戒指。另一名旅行者寫道:你可以將一段長60英尺或18米的布裝入一個小巧的鼻煙壺內。

Dhaka muslin was also more than a little transparent.

達卡平紋細布不只是有些透明。

While traditionally, these premium fabrics were used to make saris and jamas – tunic-like garments worn by men – in the UK they transformed the style of the aristocracy, extinguishing the highly structured dresses of the Georgian era. Five-foot horizontal waistlines that could barely fit through doorways were out, and delicate, straight-up-and-down “chemise gowns” were in. Not only were these endowed with a racy gauzy quality, they were in the style of what was previously considered underwear.

傳統上,這些高檔布料用於製造紗麗和類似男士短袍的衣服。但在英國,這些布料改變了貴族的穿衣風格,淘汰了喬治王時代非常有型的衣服。勉強穿過房門的五英尺寬腰身過時了,取而代之的是優雅、直上直下的“無腰身寬鬆長袍”。這種衣服不僅有輕薄透明、極具挑逗的特點,而且有曾經被認為是內衣的風格。

In one popular satirical print by Isaac Cruikshank, a clique of women appear together in long, brightly colored muslin dresses, though which you can clearly see their bottoms, nipples and pubic hair. Underneath reads the descxtion, “Parisian Ladies in their Winter Dress for 1800”.

在艾薩克·克魯克香克繪製的一幅受人喜愛的諷刺漫畫中,一羣女性身穿顏色鮮豔的平紋細布長連衣裙集體亮相,但她們的臀部、乳頭、陰毛清晰可見。圖片下面配有這樣的描述:“1800年身穿冬裝的巴黎女性”。

Meanwhile in an equally misogynistic comedic excerpt from an English women’s monthly magazine, a tailor helps a female client to achieve the latest fashion. “Madame, ’tis done in a moment,” he assures her, then instructs her to remove her petticoat, then her pockets, then her corset and finally her sleeves… “‘Tis an easy matter, you see,” he explains. “To be dressed in the fashion, you have only to undress.”

在一本英文女性月刊中,有一個同樣厭惡女性的喜劇段子,一位裁縫幫助女性顧客設計最新款式。他向她保證:“女士,馬上就好”,然後指示她脱掉襯裙、衣袋、胸衣、最後是衣袖…… “你看,這很簡單”,他解釋道。“要想穿的時尚,你就得脱光衣服”。

Still, Dhaka muslin was a hit – with those who could afford it. It was the most expensive fabric of the era, with a retinue of dedicated fans that included the French queen Marie Antoinette, the French empress Joséphine Bonaparte and Jane Austen. But as quickly as this wonder-cloth struck Enlightenment Europe, it vanished.

然而,達卡平紋細布大受歡迎——對於那些買得起的人。它是那個時代最昂貴的布料,忠實的粉絲包括法國皇后瑪麗·安託尼特、法國女王約瑟芬·波拿巴、簡·奧斯汀。但在啓蒙運動時期的歐洲,這種神奇布料流行得快,消失得也快。

By the early 20th Century, Dhaka muslin had disappeared from every corner of the globe, with the only surviving examples stashed safely in valuable private collections and museums. The convoluted technique for making it was forgotten, and the only type of cotton that could be used, Gossypium arboreum var. neglecta – locally known as Phuti karpas – abruptly went extinct. How did this happen? And could it be reversed?

20世紀初,達卡平紋細布在世界各地消失了,唯一現存的樣品被完好保存在珍貴的私人收藏和博物館中。這種布料的複雜工藝已經失傳,唯一使用的棉花是樹棉的一個變種——當地稱為普提卡帕斯——突然絕種了。為什麼會這樣?這種布料能被複原嗎?

A fickle fiber

容易變形的纖維

Dhaka muslin began with plants grown along the banks of the Meghna river, one of three which form the immense Ganges Delta – the largest in the world. Every spring, their maple-like leaves pushed up through the grey, silty soil, and made their journey towards straggly adulthood. Once fully grown, they produced a single daffodil-yellow flower twice a year, which gave way to a snowy floret of cotton fibers.

達卡平紋細布源自梅格納河岸生長的植物,它與另外兩條河流構成了巨大的恆河三角洲——世界最大的三角洲。每年春季,形似楓葉的樹葉從灰色的粉質土裏破土而出,開始蔓生的成熟之旅。當它成熟時,每年兩次開出一朵淡黃色的花,凋謝後開出雪白的棉纖維小花。

These were no ordinary fibres. Unlike the long, slender strands produced by its Central American cousin Gossypium hirsutum, which makes up 90% of the world’s cotton today, Phuti karpas produced threads that are stumpy and easily frayed. This might sound like a flaw, but it depends what you’re planning to do with them.

它們不是一般的棉纖維。不像中美洲的近親陸地棉結出細而長的纖維(佔當今世界棉花產量的90%),普提卡帕斯結出短而粗、且易受磨損的纖維。聽起來像是缺點,但這取決於你想用它做什麼。

Indeed, the short fibers of the vanished shrub were useless for making cheap cotton cloth using industrial machinery. They were fickle to work with, and they’d snap easily if you tried to twist them into yarn this way. Instead, the local people tamed the rogue threads with a series of ingenious techniques developed over millennia.

其實,消失的那種灌木結出的短纖維不適合用工業設備織造便宜的棉布。它們容易變形,捻成的棉紗容易斷裂。然而,當地人運用幾千年來發明的一系列獨創工藝駕馭了這種劣種纖維。

The full process involved 16 steps, each of which was so specialist, it was carried out by a different village around Dhaka, which was then part of Bengal – some in what is now Bangladesh, some in what is now the Indian state of West Bengal. It was a true community effort, involving the young and old, men and women.

整個工藝包含16道工序,每道工序十分專業,由達卡附近的另一座村莊來完成,地點位於當時的孟加拉——該國一部分位於當今的孟加拉國,另一部分位於當今印度的西孟加拉州。這是真正的社區工作,男女老少齊上陣。

First, the balls of cotton were cleaned with the tiny, spine-like teeth on the jawbone of the boal catfish, a cannibalistic native of lakes and rivers in the region. Next came the spinning. The short cotton fibres required high levels of humidity to stretch them, so this stage was performed on boats, by skilled groups of young women in the early morning and late afternoon – the most humid times of day. Older people generally couldn’t spin the yarn, because they simply couldn’t see the threads.

首先,他們用叉尾鮎魚顎骨上尖刺一般的牙齒清洗棉花球,這是當地河流湖泊中的一種食人魚。接下來是紡紗,短的棉纖維需要很高的濕度才能拉伸,所以這道工序由一羣技術嫺熟的年輕婦女在船上完成,時間是一天當中濕度最高的清晨和傍晚。老年人一般不紡紗,只因為看不清紗線。

“You’d get tiny, tiny little joins between the cotton fibres, where they were lixed together,” says Sonia Ashmore, a design historian who authored a book about muslin in 2012. “It lent the surface a kind of roughness, which gives a very nice feel.”

“棉纖維之間有細微的接線頭,將棉纖維連接在一起”,設計歷史學家索尼婭·阿什莫爾説道,她曾在2012年寫過一本關於平紋細布的書。“這使棉纖維表面增添了幾分粗糙,觸感很棒”。

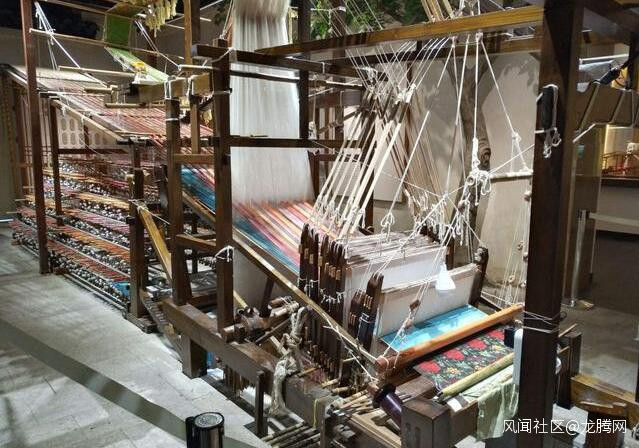

Finally, there was the weaving. This part could take months to complete, as classic jamdani designs – mostly geometric shapes depicting flowers – were integrated directly into the cloth, using the same technique that was used to create the famous royal tapestries from medi Europe. The result was a minutely detailed artwork rendered in thousands of silvery, silky strands.

最後是織造。這道工序需要幾個月來完成,典雅的堅達尼設計——多是描繪花朵的幾何圖形——直接與布料相結合,採用中世紀歐洲著名的皇家掛毯的相同工藝。最終的成品是一件細緻入微的藝術品,由數千股銀色的絲線織造而成。

An Asian wonder

亞洲的奇蹟

The region’s Western customers found it hard to believe that Dhaka muslin could possibly have been made by human hands – there were rumours that it was woven by mermaids, fairies and even ghosts. Some said that it was done underwater. “The lightness of it, the softness of it – it was like nothing we have today,” says Ruby Ghaznavi, vice president of the Bangladesh National Craft Council.

令該地區的西方客户難以置信的是,達卡平紋細布竟然是人類手工編織的——謠傳這種布料是由美人魚、仙女、甚至幽靈織造的。還有人説是在海底織造的。“布料的光澤和柔軟度——當今似乎沒有任何布料能與之媲美”,孟加拉國民族工藝委員會副主席魯比·加茲納維説道。

The same weaving process continues in the region to this day, using lower-quality muslin from ordinary cotton threads instead of Phuti karpas. In 2013, the traditional art of jamdani weaving was protected by Unesco as a form of intangible cultural heritage.

這種織造工藝在該地區一直傳承到今天,人們使用的劣質平紋細布是由一般的棉纖維製成,而不是普提卡帕斯。2013年,傳統的堅達尼紡織藝術被聯合國教科文組織列為受保護的非物質文化遺產。

But the real feat was the thread counts that could be achieved.

但是,真正的壯舉是紗線的密度。

Higher thread counts are seen as desirable because they make materials softer, and tend to wear better over time – the more strands there are to begin with, the more there will remain to hold the fabric together when some begin to fray.

較高的紗線密度是可取的,因為這使面料變得更加柔軟和經久耐用——最初使用的紗線越多,當部分紗線開始磨損時,使布料連為一體的剩餘紗線就越多。

Saiful Islam, who runs a photo agency and leads a project to resurrect the fabric, says most versions made today have thread counts between 40 and 80 – meaning they contain roughly that number of criss-crossing horizontal and vertical threads per square inch of fabric. Dhaka muslin, on the other hand, had thread counts in the range of 800-1200 – an order of magnitude above any other cotton fabric that exists today.

賽義夫·伊斯拉姆經營着一家圖片社,並負責一個旨在復原這種布料的項目,他説當今多數布料的紗線密度是40-80——意為每平方英寸布料大約包含的縱橫交錯的紗線數量。但是,達卡平紋細布的紗線密度是800-1200——這個數量級高於現存的所有棉織物。

Though Dhaka muslin vanished more than a century ago, there are still intact saris, tunics, scarves and dresses in museums today. Occasionally one will resurface at a high-end auction house such as Christie’s and Bonhams, and sell for thousands of pounds.

雖然達卡平紋細布已消失了一個多世紀,但當今博物館裏仍有保存完好的紗麗、束腰外衣、圍巾、連衣裙。偶爾會有一件在高端拍賣行重見天日,例如佳士得、寶龍,售價數千英鎊。

A colonial shambles

殖民地亂象

“The trade was built up and destroyed by the British East India Company,” says Ashmore.

“英國東印度公司建立而又毀滅了貿易”,阿什莫爾説道。

Long before Dhaka muslin was draped over aristocratic women in Europe, it was sold across the globe. It was popular with the Ancient Greeks and Romans, and muslin from “India” is mentioned in the book The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, authored by an anonymous Egyptian merchant around 2,000 years ago.

The Roman author Petronius may have been the first person on record to raise an eyebrow over its transparency, writing: “Thy bride might as well clothe herself with a garment of the wind as stand forth publicly naked under her clouds of muslin.” Over the coming centuries, the fabric is praised in the works of the renowned 14th-Century Berber-Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta and the prolific 15th-Century Chinese voyager Ma Huan, as well as many others.

早在歐洲貴族女性身穿達卡平紋細布之前,這種布料就已銷往世界各地。它深受古希臘和羅馬人的喜愛,在大約兩千年前,一位不知名的埃及商人寫過一本書叫《厄立特里亞海航行記》,其中提到了產自“印度”的平紋細布。古羅馬作家佩特羅尼烏斯可能是有史以來第一個對這種透明布料感到不滿的人,他寫道:“你的新娘相當於穿了一件輕薄如風的衣服,在多層薄紗的遮蔽下裸體露面”。在後來的幾個世紀,這種布料在許多作品中受到稱讚,例如:14世紀著名的柏柏爾-摩洛哥探險家伊本·巴圖塔、15世紀創作豐富的中國航海家馬歡等等。

But the Mughal era was arguably the fabric’s heyday. The South Asian empire was founded in 1526 by a warrior chieftain from what is now Uzbekistan, and by the 18th Century it ruled across the entire Indian subcontinent. During this period, muslin was traded extensively with merchants from Persia (modern-day Iran), Iraq, Turkey and the Middle East.

但是,莫卧兒帝國是這種布料的鼎盛時期。1526年,地處當今烏茲別克斯坦的一位武士首領建立了這個南亞帝國。到了18世紀,該帝國統治着整個印度次大陸。在這一時期,平紋細布被商人大量買賣,他們來自波斯(當今伊朗)、伊拉克、土耳其、中東地區。

The cloth was thoroughly endorsed by Mughal emperors and their wives, who were rarely painted wearing anything else. They went so far as to bring the best weavers under their patronage, employing them directly and banning them from selling the very finest cloth to others. According to popular legend, its transparency led to yet more trouble when the emperor Aurangzeb scolded his daughter for appearing in public naked, when she was, in fact, ensconced in seven layers of it.

這種布料受到莫卧兒皇帝及其妻子的大力支持,他們在繪畫作品中很少穿着其他布料。他們不遠萬里請來和資助最好的織布工,直接僱傭他們,禁止他們把最好的布料賣給別人。民間傳説這種透明的布料引起了更多麻煩,奧朗則布皇帝斥責女兒裸體公開露面,其實她身穿的平紋細布有七層。

It was all going so well – then the British turned up. By 1793, the British East India Company had conquered the Mughal empire, and less than a century later the region was under the control of the British Raj.

一切都很順利——然後英國人來了。1793年,英國東印度公司征服了莫卧兒帝國,不到一個世紀,英國就統治了這片地區。

Dhaka muslin was first showcased in the UK at The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in 1851. This spectacular event was the brainchild of Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert, intended to showcase the wonders of the British Empire to their subjects. Some 100,000 obxts from the farthest corners of the globe were gathered together in a glittering glass hall, Crystal Palace, which was 1,851ft (564m) long and 128ft (39m) high.

1851年,英國舉辦的萬國工業博覽會首次展示了達卡平紋細布。這一盛況是維多利亞女王的丈夫艾伯特親王的創意,旨在向臣民展示大英帝國的奇蹟。天南海北近十萬件物品被共同展示在晶瑩剔透的玻璃大廳“水晶宮”裏,長1851英尺(564米),高128英尺(39米)。

At the time, a yard of Dhaka muslin fetched prices ranging from £50-400, according to Islam – equivalent to roughly £7,000-56,000 today. Even the best silk was up to 26 times less expensive.

當時,每碼達卡平紋細布售價50-400英鎊,根據賽義夫·伊斯拉姆的説法——約合當今7000-56000英鎊,比當時最上乘的布料還要貴26倍。

But while Victorian Londoners were fawning over the fabric, those who produced it were being pushed into debt and financial ruin. As the book Goods from the East, 1600–1800 explains, the East India Company first started meddling with the delicate process of manufacturing Dhaka muslin in the late 18th Century.

但是,雖然維多利亞時代的倫敦人對這種布料讚賞有加,但布料生產者卻被迫負債和破產。正如《來自東方的商品》這本書所描述的,18世紀末,英國東印度公司開始干預達卡平紋細布精湛的生產工藝。

First the company replaced the region’s usual customers with those from the British Empire. “They really put a stranglehold on its production and came to control the whole trade,” says Ashmore. Then they came down hard on the industry, pressurising the weavers to produce higher volumes of the fabric at lower prices.

首先,該公司以大英帝國的客户代替該地區的老客户。“他們完全壟斷生產,控制整個貿易”,阿什莫爾説道。隨後他們對行業變得苛刻,逼迫織布工低價生產更多的布料。

“You needed such a special skill to convert it [Phuti karpas] into cloth,” says Islam. “It’s a very arduous, expensive process – and at the end of the day, after all that you’d only get about eight grammes of fine muslin for one kilogramme of cotton.”

“你需要特殊技能才能將它(普提卡帕斯)轉化為布料”,伊斯拉姆説道。“這是一種既艱難又昂貴的織造工藝——最終每千克棉花只能織出大約8克平紋細布”。

As weavers struggled to keep up with these demands, they fell into debt, explains Ashmore. They were paid upfront for the cloth, which could take up to a year to make. But if the fabric was not considered to be up to the required standard, they would have to pay it all back. “They could never really keep up with these debt repayments,” she says.

隨着織布工吃力地滿足需求,他們負債累累,阿什莫爾説道。他們收取預付費來生產布料,生產週期可能需要一年。但如果布料被認為沒達到規定的標準,他們必須全款賠償。“他們根本無力償還這些債務”,她説道。

The final blow came from competition. Colonial enterprises such as the East India Company had been engaged in documenting the industries they relied on for years, and muslin was no exception. Every step of the process of making the fabric was recorded in meticulous detail.

最後一次打擊來自競爭。多年來,東印度公司這樣的殖民企業一直詳細記載它們依賴的各個行業,平紋細布也不例外。他們記錄了織造這種布料的每一道工序的細節。

As the European thirst for luxury fabrics increased, there was an incentive to make cheaper versions closer to home. In the county of Lancashire in northwest England, the textile baron Samuel Oldknow combined the British Empire’s insider knowledge with state-of-the-art technology, the spinning wheel, to supply Londoners with vast quantities. By 1784, he had 1,000 weavers working for him.

隨着歐洲對奢華布料的需求增加,推動他們在接近本土的地方織造更便宜的布料。在英格蘭西北部的蘭開夏郡,紡織大亨塞繆爾·歐德諾將大英帝國的內部知識與技術先進的紡車相結合,為倫敦人供應大量的布匹。1784年,他僱傭了1000名織布工為他效勞。

Though the British-made muslin didn’t come close to Dhaka’s original – it was made with ordinary cotton, and woven at significantly lower thread counts – the combination of decades of mistreatment and a sudden decline in the need for imported textiles killed it off for good.

但是,英國織造的平紋細布與達卡原版布相差甚遠——使用普通棉花織造,紗線密度嚴重下降——幾十年的苛刻行為和進口紡織品需求的突然下降使這種布料徹底消失了。

As war, poverty, and earthquakes struck the region, some weavers switched to making lower-quality fabrics, while others became full-time farmers instead. In the end, the whole enterprise collapsed.

隨着該地區遭受戰爭、貧窮、地震,部分織布工轉而織造劣質布料,其餘織布工成了地道的農民。最終,整個產業崩潰了。

“I think it’s important to remember that it was really a family occupation – we often talk about the weavers and how fantastic they were, but behind their work was the women, doing the spinning,” says Hameeda Hossain, a human rights activist who has written a book about the muslin industry in Bengal. “So the industry involved a lot of people.”

“我認為,記得這是一種真正的家庭作坊很重要——我們總是談論那些了不起的織布工,但他們的後盾是紡紗婦女”,人權活動人士哈米達·侯賽因説道。他曾寫過一本有關孟加拉平紋細布產業的書籍。“所以這個產業有大量的人力參與”。

As the generations passed, the knowledge of how to make Dhaka muslin was forgotten. And with no one to spin its silky threads, the phuti karpas plant, which had always been hard to tame – no one had been able to grow it away from the Meghna river – retreated back into wild obscurity. The legend of the loom was no more.

隨着幾代人的逝去,織造達卡平紋細布的知識失傳了。由於沒有人紡織普提卡帕斯這種難以駕馭的絲線——沒有人能夠在梅格納河岸以外的地方種植普提卡帕斯——結果退化到默默無聞的野生狀態。織布機的傳奇不復存在。

A second chance

第二次機會……