周波:美國做出這種事,印度該吸取教訓了

【文/ 周波】

4月7日,當美軍一艘9000噸級導彈驅逐艦"約翰·保羅·瓊斯"號出現在印度專屬經濟區(EEZ)內,在拉克夏德韋普羣島以西約130海里處宣稱擁有航行自由權時,印度吃了一驚。

印度外交部對此次突如其來的行動表示吃驚並提出了“温和”的抗議,稱這次行動是未經許可的。它還表示,其擔憂已"通過外交渠道"傳遞給華盛頓。

如果印度有選擇餘地—假設美國海軍不聲張此事—新德里很可能會假裝什麼都沒發生。然而,這一事件發生在首次“四方安全對話峯會”後不到一個月,又是美國總統氣候特使克里訪問新德里期間,因此不容忽視。

近年來,印度和美國一直高唱"自由開放的印太",但並不是心心相印。挑戰印度專屬經濟區的決定表明,華盛頓並不認為印度洋數百萬平方公里的水域是"自由開放的"。

美海軍阿利·伯克級驅逐艦“約翰·保羅·瓊斯”號資料圖片(資料圖)

俾斯麥據説有一句名言,“法律就像香腸,最好不要看它們被製作的過程”。《聯合國海洋法公約》(以下簡稱“公約”)可能是有史以來製作的最長的“香腸”。談判進行了九年,可想而知,公約不乏妥協之處,若干模稜兩可的地方可被靈活解讀。

自1982年公約通過以來,將近40年過去了。美國還沒有批准公約,但它的所作所為卻儼然是海洋法的守護者。根據五角大樓的説法,從2019年10月1日到2020年9月30日,美軍以行動挑戰了"全球19個不同聲索國提出的28項不同的過度海洋主張"。

一個簡單的問題冒出來了: 如果公約很好,為什麼美國還沒有批准?如果公約不好,為什麼美國要以它的名義挑戰別國?

德里警惕地將印度洋作為自己的後院來守護,對中國在印度洋日益增長的影響力感到不滿,這已不是什麼秘密了。印度外長蘇傑生説,去年印中兩國士兵在邊境地區的加勒萬河谷發生的致命鬥毆,使印度對中國的信任"受到嚴重干擾"。

但當德里模仿華盛頓兜售"自由開放的印太"時,幾乎產生了喜劇效果。因為在國際海洋法方面,印度與中國的共同點多於印度與美國的共同點。

例如,與印度一樣,中國不接受公約第298條所述的所有爭端的仲裁。印度在向美國提出抗議時表示,它認為"該公約沒有授權其他國家在未經沿岸國同意的情況下在其專屬經濟區和大陸架進行軍事演習或演訓,特別是涉及武器或爆炸物的軍事演習或演訓"。

與印度一樣,中國也關注外國在其專屬經濟區的軍事活動。中國對美軍高強度和大範圍的抵近偵察提出了批評。中國和印度的立場並不是孤立的。世界上有20多個國家對外國在其專屬經濟區內的軍事活動有不同程度的限制。

不過,一個關鍵的區別是,北京對美國行徑的反應是強有力的,這與德里大相徑庭。至少從1992年起,美國一直在針對印度的海洋主張進行“航行自由行動”(Fonops),但"(印度)政府和海軍更願意對美國在專屬經濟區的行動保持沉默“,印度分析師馬諾伊·喬希在2019年寫道,“沒有印度海軍試圖阻撓美國軍艦的記錄“。

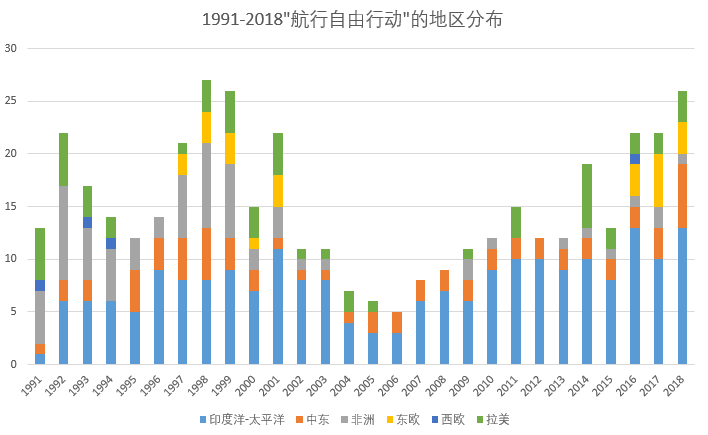

1991-2018“航行自由行動”的地區分佈(圖源:中國南海研究院)

中國則有從抗議、艦對艦警告到攔截等的各層級反應,尤其是當美國軍艦進入中國南海島礁附近12海里領海時。在海上已經發生了許多危險的遭遇。

我曾在一次國際會議上問一位美國海軍高級軍官,中美兩國如何防止在南海發生雙方都不想要的事故。他毫不猶豫地回答:“中國艦長想説什麼就説什麼, 但不要擋我的道“。

這是不可能的。如果美國在中國南海水域增加“航行自由行動”頻次,越來越強大的中國人民解放軍海軍只會更加堅決地遏制它們。因此,至少從理論上講,另一場危機的發生只是時間問題。

馬凱碩在其《中國贏了嗎》一書中假設,到2050年,當中國經濟規模實際是美國經濟規模的兩倍時,美軍可能會離開西太平洋,撤回到西半球距中國11,000公里之遙的地方。也許吧!但在那之前會發生什麼呢?

對北京來説,一個根本性的問題是:如果美國想要止沸,為什麼還要一直往火裏填柴?是美國軍艦定期到中國家門口挑釁,而不是中國軍艦到美國家門口挑釁。

目前尚不清楚,在華盛頓與中國展開競爭並希望德里站在自己一邊之際,美國海軍為何選擇宣揚其在印度專屬經濟區的行動。這對印度來説是一個有用的教訓:權宜之計可能會在短期內奏效,但從長遠看,它很少會有回報,更糟糕的是,它還可能引火燒身。

(本文原載於2021年5月6日《南華早報》,英文原作見下)

Why India’s maritime interests are closer to China than the US

India was surprised when the USS John Paul Jones, a 9,000-tonne guided missile destroyer, asserted navigational rights some 130 nautical miles west of the Lakshadweep Islands on April 7, inside India’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), without requesting prior consent.

Taken aback by the suddenness of the operation, India’s Ministry of External Affairs made a mild protest, saying the operation was unauthorised. It also said its concerns had been conveyed to Washington “through diplomatic channels”.

If India had a choice – that is, if the US Navy made no mention of it – New Delhi would probably have pretended nothing had happened. However, the fact the incident took place less than a month after the first Quad summit and during US presidential climate envoy John Kerry’s visit to New Delhi was too much to ignore.

India and the United States have been part of the chorus chanting about the “free and open Indo-Pacific” in recent years, but they are not birds of a feather flocking together. The decision to challenge India’s EEZ suggests that Washington does not consider millions of square kilometres of water in the Indian Ocean “free and open”.

Otto von Bismarck is famously reported to have said, “Laws are like sausages, it is better not to see them being made.” The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos) is probably the longest sausage ever made. It was negotiated for nine years, and understandably compromises were made and ambiguities that could be flexibly interpreted were found.

Almost four decades have passed since the convention was adopted in 1982. The US still has not ratified the convention, yet it behaves as if it is the guardian of maritime law. From October 1, 2019 to September 30, 2020, US forces operationally challenged “28 different excessive maritime claims made by 19 different claimants throughout the world”, according to the Pentagon.

A simple question arises. If the convention is good, why hasn’t the US ratified it? If it is not good, why would the US challenge others in the name of it?

It is no secret Delhi is not happy with China’s growing influence in the Indian Ocean, which India jealously guards as its own backyard. The deadly brawl between Chinese and Indian soldiers in the Galwan Valley in the border areas last year made its trust towards China “profoundly disturbed”, as Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar said.

But when Delhi mimics Washington to tout the “free and open Indo-Pacific”, it almost has a comedic effect. India has more in common with China than with the US when it comes to international maritime law.

For example, like India, China does not accept arbitration on all disputes referred to in Article 298 of the convention. In its protest to the US, India said it believed “the convention does not authorise other states to carry out military exercises or manoeuvres, in particular those involving weapons or explosives, without the consent of the coastal state in the exclusive economic zone and on the continental shelf”.

Like India, China is concerned with foreign military activities in its EEZ. China has criticised America’s high intensity and large scale close-in reconnaissance. China and India are not alone. More than 20 countries in the world have restrictions on foreign military activities in their EEZs, to varying degrees.

A key difference, though, is that Beijing’s response to America’s behaviour is robust, unlike that of Delhi. The US has conducted freedom of navigation operations (Fonops) directed at Indian maritime claims since at least 1992, but “the [Indian] government and navy prefer to remain silent on US operations in the EEZ”, Indian analyst Manoj Joshi wrote in 2019. “There is no record of the Indian Navy having attempted to thwart US Navy ships.”

China’s response ranges from protests and ship-to-ship warnings to interceptions, particularly when American ships enter into the 12-nautical-mile territorial waters off Chinese rocks and islands in the South China Sea. There have been a number of dangerous encounters at sea.

I once asked a senior American naval officer at an international conference how China and the US might prevent accidents that neither wants in the South China Sea. Without hesitation he said, “The Chinese ship commander can say whatever he wants, but don’t sail in my way.”

This is impossible. If American Fonops increase in China’s waters in the South China Sea, an ever-stronger PLA Navy can only become more determined to check them. Therefore, at least in theory, it is only a matter of time before another crisis occurs.

In Kishore Mahbubani’s book Has China Won?, he assumes that by 2050, when the Chinese economy could effectively be twice as large as the US economy, America could withdraw from the western Pacific Ocean and retreat back into its hemisphere and live 11,000km away from China. Maybe. But what would happen before then?

For Beijing, a fundamental problem exists – if the US does not want the water to boil, why does it keep throwing wood into the fire? It is the American ships that come regularly to China’s doorstep and not the other way round.

It is not clear why the US Navy chose to publicise its operation in India’s EEZ at a time when Washington wants Delhi to take its side in its competition with China. It is a useful lesson for India. Expediency might sell in the short term, but it seldom pays off in the long run and, worse still, it might backfire.

Senior Colonel Zhou Bo (ret) is a senior fellow at the Centre for International Security and Strategy at Tsinghua University and a China Forum expert

本文系觀察者網獨家稿件,文章內容純屬作者個人觀點,不代表平台觀點,未經授權,不得轉載,否則將追究法律責任。關注觀察者網微信guanchacn,每日閲讀趣味文章。