諾獎得主Wilczek:在缺陷上前進_風聞

返朴-返朴官方账号-关注返朴(ID:fanpu2019),阅读更多!2022-02-16 13:01

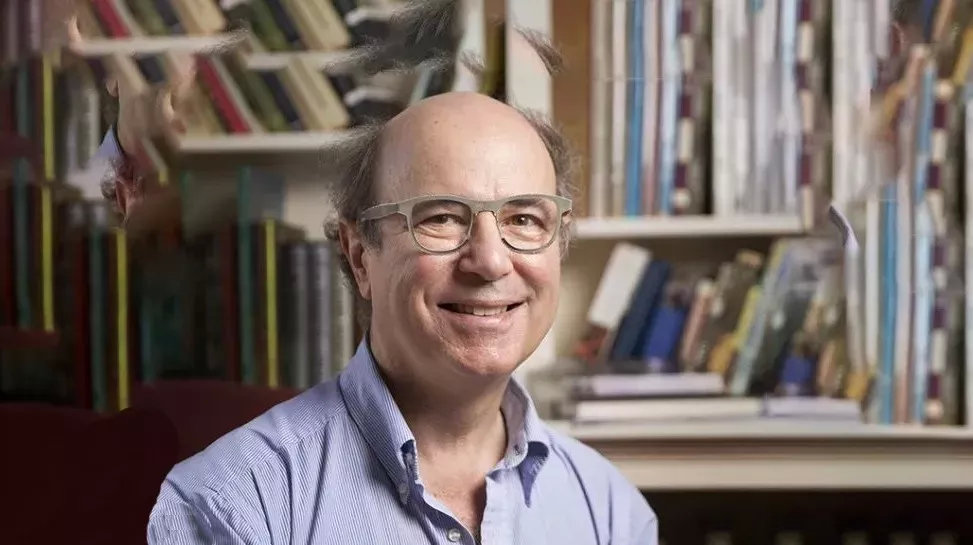

弗蘭克·維爾切克是麻省理工學院物理學教授、量子色動力學的奠基人之一。因發現了量子色動力學的漸近自由現象,他在2004年獲得了諾貝爾物理學獎。

弗蘭克·維爾切克是麻省理工學院物理學教授、量子色動力學的奠基人之一。因發現了量子色動力學的漸近自由現象,他在2004年獲得了諾貝爾物理學獎。

撰文 | Frank Wilczek

翻譯 | 胡風、梁丁當

中文版

構建複雜模型往往會帶來新的突破,哪怕模型最終是有缺陷的。

構建複雜模型往往會帶來新的突破,哪怕模型最終是有缺陷的。

著名物理學家理查德 · 費曼(Richard Feynman)的黑板上,一個個數學式子和電報似的任務清單寫了又擦,擦了又寫。唯有一句話始終保留在黑板的左上角 :“如果我不能創造,我就沒有真正理解。”直到1988年費曼去世,這句話仍留在他的黑板上。我不知道這句話到底對費曼意味着什麼。但我猜,它某種程度上是一種自我告誡 :“構建模型!”

這句箴言深植於科學實踐。但在科學發展史上,這種研究方式可謂譭譽參半。著名的托勒密的“天球”和詹姆斯·克拉克 · 麥克斯韋(James Clerk Maxwell)的“機械以太”就是兩個典型的例子。

托勒密的著作《至大論》完成於公元150年,一直到16世紀它依然是天文學的最高數學理論。著作的核心是一個精心構建的模型,用來模擬肉眼觀測到的恆星、太陽、月亮以及水星、金星、火星、木星和土星等行星在天空中的運動。這些天體嵌在一個個大小不一、旋轉速度不同的輪子上。其中一些輪子繞着另一個更大的輪子旋轉,後者又再繞着另一個輪子旋轉,形成所謂的本輪。在托勒密的數據驅動體系中,地球被賦予特殊的地位,固定在模型的中心。

尼古拉斯 · 哥白尼(Mikołaj Kopernik)的研究基於托勒密體系,卻最終在根本上撼動了托勒密體系。他注意到在托勒密本輪的大小和旋轉之間存在着一種系統性的聯繫。在托勒密體系中,這些聯繫不過是某種神秘的巧合。但哥白尼發現,如果在模型中允許地球以兩種方式運動 :每天繞軸轉動,每年繞太陽運行,則這種聯繫就會自動滿足。哥白尼的創新最終導致了對天體運動截然不同的解釋 ;在牛頓的經典體系中,沒有虛構的本輪,只有真實物體和描述它們的普適定律。它不再只是模型,而是赤裸裸的現實。

19世紀時,麥克斯韋為了嘗試理解電磁現象,設想了一個與眾不同的機械模型。他想象空間中堆滿了看不見的滾擺和齒輪,它們忠實地傳遞着電磁的力和能量。通過計算,麥克斯韋驚訝地發現這些假想機械中的擾動居然以光速進行傳播。他大膽地推斷光是一種電磁擾動。後來,麥克斯韋拋棄了他的滾擺齒輪模型,提煉出了一組關於可觀測的電場和磁場的普適定律。這就是我們今天使用的所謂麥克斯韋方程組。又一次,當真相如光芒噴薄而出,那些雜亂無章的模型也隨之煙消雲散。

傳統的科學著作和論文往往對成熟的結果津津樂道,而忽視產生結果的曲折而充滿錯誤的過程。所謂的科學“輝格派”對虛構的托勒密“本輪”模型和麥克斯韋“機械以太”模型嗤之以鼻。然而,如果沒有托勒密精密的數學建模,哥白尼的革新和牛頓的發現也就無從談起。

同樣地,麥克斯韋的建模給他提供了一個“腳手架 ”:在最後被拆除前,它讓麥克斯韋有了一個可以搭建理論的工作平台。在現代科學中,我們通過剪裁已有的材料與設計人工超材料來實現電磁場調控,這與麥克斯韋的思想一脈相承。

在一線工作的科學家喜歡宣傳“獨立於模型”的結果,而略過導致這些結果的混亂的創造性思維過程。這為讀者節省了時間,也讓科學家看起來很聰明。但當結果真的很重要的時候,瞭解這些結果誕生的過程不僅有趣也富有啓發意義。詹姆斯·沃森(James Watson)在他的回憶錄《雙螺旋》(The Double Helix)中坦露了他發現DNA結構的曲折經歷,讓我們如獲至寶。

我收到過的一個最好的幸運餅,其中有一句類似費曼格言的籤語 :“實踐出真知。”這是一個睿智的建議,無論科學還是生活,都是如此。

英文版

The work of constructing elaborate systems often leads to breakthroughs—even when the systems themselves turn out to be flawed.

The work of constructing elaborate systems often leads to breakthroughs—even when the systems themselves turn out to be flawed.

The blackboard of the famed physicist Richard Feynman mostly featured an everchanging mix of math and telegraphic to-do lists. But in the upper left-hand corner a boxed sentence lingered for years: “What I cannot create I do not understand.” It was still there when he died, in 1988. I don’t know exactly what that sentence meant to Feynman, but I suspect it was partly a self-reminding exhortation:“Make models!”

That advice has deep roots in scientific practice. It’s got a mixed reputation, though. Two famous historical examples, featuring Ptolemy’s “celestial spheres” and James Clerk Maxwell’s “mechanical ether,” show why.

Ptolemy’s treatise “Almagest” (Arabic for “The Greatest”) was the state of the art in mathematical astronomy from its genesis around the year 150 into the 16th century. Its centerpiece was an elaborate model that reproduced the observed motion of objects seen in the sky by the naked eye—stars, the sun, the moon, and the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. They were carried along by celestial spheres of different sizes, rotating at different rates. Some of the spheres had to roll onto other spheres, which rolled onto still others, making so-called epicycles. In Ptolemy’s data-driven system, Earth was taken to be a fixed vantage point at the center.

Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543), whose work ultimately undermined Ptolemy’s system, originally built upon it. He noticed systematic relationships among the sizes and rotations of Ptolemy’s spheres. Within Ptolemy’s system those relationships were mysterious coincidences, but Copernicus found that they followed automatically if one’s model allowed Earth to move in two ways: daily around an axis and yearly around the Sun. Copernicus’s reforms ultimately led to a radically different account of celestial motion; in Newton’s classical system there are no imaginary celestial spheres, but only physical bodies and universal laws. It is no mere model, but reality laid bare.

In the 19th century James Clerk Maxwell, striving to understand electricity and magnetism, imagined a different mechanical model. Maxwell’s space-filling mishmash of invisible wheels and gears faithfully transmitted the energies and forces of electrcity and magnetism. Amazingly, Maxwell discovered (by calculation) that disturbances within his machine spread at the observed speed of light. He boldly deduced that light is an electromagnetic disturbance. Later Maxwell dispensed with his wheels and gears, to distill a set of universal laws that only involve things we can observe, namely electric and magnetic fields. These are the so-called Maxwell equations that we use today. Here again, revealed reality blew away kludgy models.

Traditional science texts tend to celebrate mature results, while deprecating the meandering, often erratic processes that led to them. That so-called “Whiggish” tradition of science disdains the clutter of Ptolemy’s “epicycles” and Maxwell’s “mechanical ether.”Yet without Ptolemy’s mathematically precise modeling, Copernicus’s reforms and Newton’s revelations would have been unthinkable—literally.

Likewise, Maxwell’s modeling gave him a scaffolding he could build on (and later jettison). Its spirit lives on in the modern science of crafting known materials—and designing “meta-materials” —to sculpt the behavior of electromagnetic fields.

Practicing scientists like to advertise “modelindependent” results and suppress the messy creative thought processes that led to them. This saves time for readers, and makes the scientists look clever. But when results are truly important, it’s entertaining and instructive to find out how people got to them. James Watson’s memoir “The Double Helix” aired his dirty linen around discovering the structure of DNA and gifted us a gem.

My best-ever fortune cookie contained a variant of Feynman’s maxim: “The work will teach you how to do it.” It is wise advice, in science as in life.

本文經授權轉載自微信公眾號“蔻享學術”。

特 別 提 示

1. 進入『返樸』微信公眾號底部菜單“精品專欄“,可查閲不同主題系列科普文章。

2. 『返樸』提供按月檢索文章功能。關注公眾號,回覆四位數組成的年份+月份,如“1903”,可獲取2019年3月的文章索引,以此類推。