周波:所謂“美國領導的自由國際秩序”是子虛烏有,世界之美在於豐富多樣

【文/周波 譯/中國論壇 孫一葦 核譯/許馨勻、韓樺】

中國和美國是否正處於不可避免的相撞軌道上?把美國總統拜登10月12日發佈的《國家安全戰略》與四天後習近平總書記在中國共產黨第二十次全國代表大會上所作的報告進行比較,人們可能會有這樣的疑問。

拜登總統斷言,中國不僅有重塑國際秩序的意圖,而且日益有能力將之付諸實踐,他還放言要“勝過”中國。習近平總書記未點名美國,但他警示説,前進道路上“風高浪急甚至驚濤駭浪”,並明確指出,全黨同志務必敢於鬥爭,善於鬥爭。

由於美國一意孤行想在各條戰線上進行競爭,華盛頓與北京在諸如氣候變化等問題上合作的提議,似乎是茫茫大海中的一個小島。拜登説對了一件事:未來十年將是決定性的十年。

即使所有跡象都表明北京和華盛頓之間的競爭接下來會變得更加激烈,但是結果已經大致清楚。按購買力平價計算的國內生產總值(GDP),中國在2013年就超過了美國。

儘管放緩的增長抑制了對中國經濟在2030年前躍居為全球最大經濟體的預期,但很大的可能性是,中美差距將持續縮小,最終雙方在不同領域各有領先,達成某種平衡。

競爭更多關乎心態。當拜登談論國際秩序時,他實際上是在説他此前所稱的“自由國際秩序”,其中美國的領導地位被視作理所當然。但這種秩序在世界上並不存在。

誠然,許多規則、制度,甚至像國際貨幣基金組織和世界銀行這樣的機構都是西方在二戰後量身打造的,但僅僅這些並不能定義一個由風起雲湧的非洲獨立運動、冷戰、蘇聯解體和中國崛起等重大事件塑造的體系。

從本質上來説,國際秩序包括不同的宗教、文化、習俗、民族特性和社會制度,其中一些可能已經存續千年之久。國際秩序還受到全球化、氣候變化、大流行病和核擴散的影響。

事實上,看似最接近自由國際秩序的時期是蘇聯解體後的15年左右,當時中國還沒有完全崛起。然而這在人類歷史上不過是彈指一揮間。

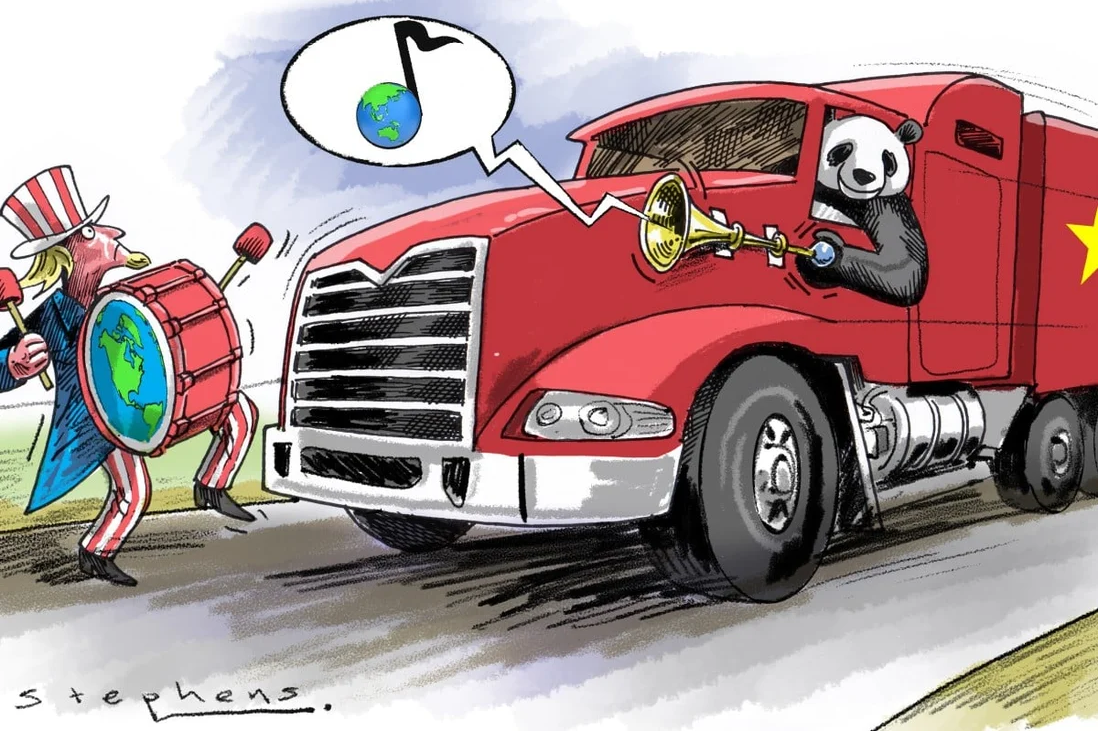

中國正在挑戰美國領導下的“自由國際秩序”(作者供圖)

如果沒有自由國際秩序,就不會有“民主與專制”的簡單二分法。根據《經濟學人》智庫發佈的2021年“民主指數”,在總共167個國家和地區中,只有21個被認為是完全的“民主國家”,佔世界人口的6.4%。如果“自由民主”模式站在道德的制高點上,那怎麼解釋為什麼它在全球都出現衰退呢?

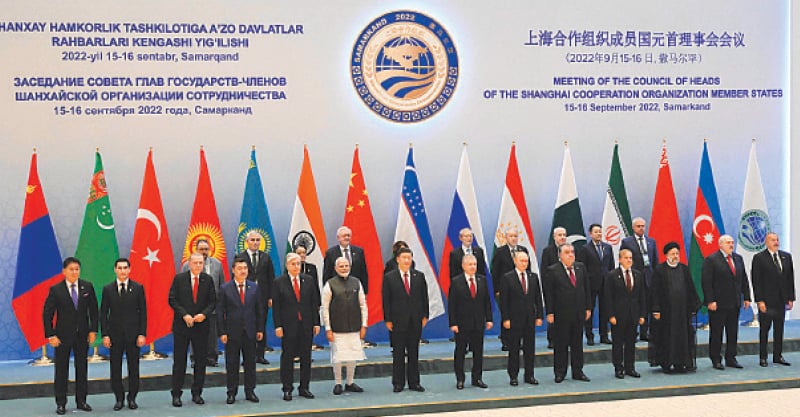

“自由國際秩序”不能解釋為什麼像印度這樣的民主國家被認為變得越來越專制;不能解釋為什麼由中國和俄羅斯這兩個所謂“威權國家”領導的上海合作組織正在發展壯大,甚至吸引了土耳其這個北約國家;不能解釋為什麼美國前總統特朗普煽動暴民佔領美國民主的最高殿堂國會山;不能解釋為什麼中國在保有自己的社會制度的同時,已經與世界其他地區緊密相連。

北京和華盛頓之間的真正競爭,不是如何在國內勝過對方,而是如何在其他地方贏得民心。在美國正集結力量的印度—太平洋地區,日本和澳大利亞乍一看像是美國的鐵桿盟友。

但現在就斷定它們會對美國俯首帖耳、與它們最大的貿易伙伴作對,還為時過早。在東南亞,各國擔心不得不在兩個巨頭之間選邊站隊。雖然中印關係在兩年前的邊境衝突後仍在低谷,但2021年的雙邊貿易額創下了1256億美元的歷史新高。

在非洲和拉丁美洲,中國的快速發展激勵人心。公眾對中國的區域經濟和政治影響力的態度基本上是積極的,部分原因是中國有一些獨特的經驗可資借鑑——如何在40年內使8億人脱貧。這些經驗應該比西方空洞的道德説教更有用。

仍然不太確定的是中歐關係。但即使歐盟將中國列為“系統性對手”,只要中國和俄羅斯不結盟,台灣海峽不發生衝突,中歐關係大體上仍會保持穩定。此外,烏克蘭衝突將加速全球重心向亞太地區轉移。因此,歐洲將愈加轉向東方。

冷戰的一個很好的教訓是,即使是敵人有時也可以合作。中國和美國還不是敵人。而競爭對手要想不成為敵人,需要的是迴歸常識——無論我們有多麼不同,我們必須共存。人們看一眼花園,就會意識到,世界之美在於豐富多樣。

原文:

China’s growing global links show there is no such thing as a US-led international order

Are China and the US on an inevitable collision course? One may wonder this when comparing the National Security Strategy issued by American President Joe Biden on October 12 with the report of the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party delivered by President Xi Jinping four days later.

President Biden asserted that China harbours the intention and, increasingly, the capacity to reshape the international order and vowed to “outcompete” China. Without naming the US, President Xi Jinping warned of “high winds, choppy waters and even dangerous storms” on the journey ahead and made it clear that China has the courage and ability to carry on its fight.

With the US hell-bent on competition on all fronts, Washington’s offer to cooperate with Beijing on issues such as climate change appears as a tiny isle in a vast ocean. Biden is right about one thing: the next 10 years will be the decisive decade.

But even if all signs point to competition between Beijing and Washington becoming fiercer down the road, the outcome is very much known already. China’s gross domestic product (GDP) in PPP terms overtook that of the US in 2013.

Although slow growth has dampened expectations that the Chinese economy will be the largest by the end of the decade, the high probability is that the gap between the US and China will continue to shrink until a kind of balance is achieved, with each leading in different areas.

Competition is more about mentality. When Biden talks about the international order, he is actually talking about what he has previously referred to as the “liberal world order”, in which America’s leadership is taken for granted. There is no such order in the world.

True, many rules, regimes and even institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank were tailor-made by the West after World War II, but these alone do not define a system shaped by major events such as the independence movements in Africa, the Cold War, the fall of the Soviet Union and the rise of China, to name just a few.

Intrinsically, the international order comprises different religions, cultures, customs, national identities and social systems. Some of them may have survived over a millennium. It is also affected by globalisation, climate change, pandemics and nuclear proliferation.

In fact, the period that looks at best like a liberal international order is the 15 years or so after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when China had yet to rise fully. This is but a blink of an eye in human history.

If there is no liberal international order, there can be no simplistic dichotomy of “democracy vs autocracy”. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index 2021, just 21 territories out of a total of 167 were deemed to be full democracies, representing 6.4 per cent of the world’s population. If the liberal democratic model stands on a moral high ground, this does not explain why there is a global decline in democracy.

It does not explain why a democracy like India is considered increasingly authoritarian. It does not explain why the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation led by China and Russia – two “authoritarian states” – is growing and has even attracted Türkiye, a Nato country. It does not explain why former American president Donald Trump instigated mobs to take over Capitol Hill, the highest seat of American democracy. It does not explain why China, while preserving its own social system, has become integrated with the rest of the world.

今年9月,土耳其等國領導人出席上合成員國元首理事會會議(圖源:Dawn)

The real competition between Beijing and Washington is not how to outperform each other at home, but to win the hearts and minds of people elsewhere. In the Indo-Pacific, where the US is rallying forces, Japan and Australia look like diehard American allies at first glimpse.

But it is premature to conclude they will follow the US willy-nilly in going against their largest trading partner. In Southeast Asia, countries fear having to take sides between the two giants. Although Sino-India relations are still frosty following a border clash two years ago, bilateral trade hit a record high of US$125.6 billion in 2021.

In Africa and Latin America, China’s fast-paced development makes it an inspiration. Public sentiment towards China’s regional economic and political influence is largely positive, in part because China has some unique lessons to teach on how it lifted 800 million people out of poverty in 40 years. These lessons should be more useful than hollow Western moralising.

What remains uncertain is China’s relationship with Europe. But even if the EU makes China a “systemic rival”, it seems likely that, so long as China and Russia don’t form an alliance and there is no conflict in the Taiwan Strait, the China-European relationship will by and large remain stable. Moreover, the conflict in Ukraine will expedite the shift of the global centre of gravity to the Asia-Pacific. As a result, Europe will look increasingly more to the East.

A good lesson from the Cold War is that even enemies can cooperate sometimes. China and the US are not enemies yet. And for competitors to not become enemies, they just need the common sense to know that however different we are, we must coexist. One only needs to look at a garden to know the beauty of the world lies in diversity.

Senior Colonel Zhou Bo (ret) is a senior fellow of the Centre for International Security and Strategy at Tsinghua University and a China Forum expert.

This article was first published on South China Morning Post on Nov. 8, 2022.

本文系觀察者網獨家稿件,文章內容純屬作者個人觀點,不代表平台觀點,未經授權,不得轉載,否則將追究法律責任。關注觀察者網微信guanchacn,每日閲讀趣味文章。